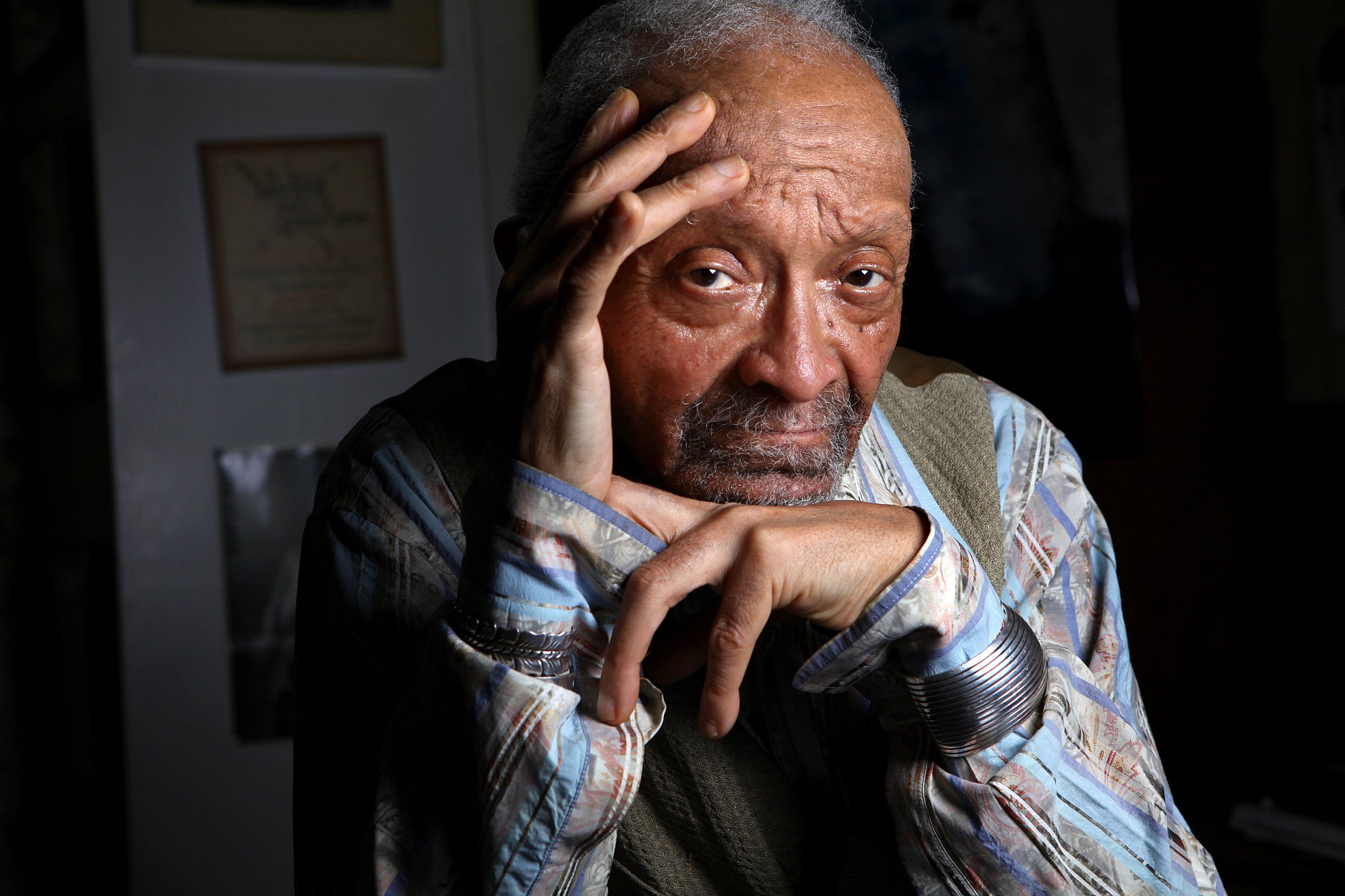

Cecil Taylor

Photo: Chester Higgins, Jr./The New York Times

Cecil Taylor was born on March 25, 1929 (to April 5, 2018). He was a celebrated jazz pianist and poet who is generally acknowledged as one of the pioneers of free jazz.

Cecil Percival Taylor was born in Queens, New York, the child of a musical family, whose mother was a dancer and silent film actress. She also played the piano and violin, but died of cancer while Taylor was still young. His father, Percy Clinton Taylor, was head chef at the Rivercrest Sanitarium in Astoria. When he came home from his 17-hour work day during the week, Taylor’s father sang hymns, and listened to popular performers. Cecil Taylor has said he liked to hear his father sing “shouts and things that go back farther than the blues.” From the age of five, the younger Taylor studied piano and percussion with a classical tutor, and briefly played drums. He grew up listening to Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and Erroll Garner. Among Taylor’s early influences were Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

Taylor attended the New York College of Music and The New England Conservatory of Music in the early 1950s. After forming some R&B and swing-styled groups in the early fifties, he began leading his own small groups with musicians Buell Niedlinger, Steve Lacy, and Archie Shepp. In 1957, Taylor played the Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island, and New York’s Great South Bay Jazz Festival the following year. In 1966, Blue Note released two outstanding sessions: “Unit Structures” and “Conquistador” (with Bill Dixon on trumpet). Taylor, along with Bill Dixon, was one of the organizers of the Jazz Composers Guild in 1964-65.

Taylor’s earliest work was with more conventional swing and be-bop ensembles, but small groups he assembled himself during this period were used to begin his exploration into new, untouched territory. The further into this territory that Taylor went, the harder it was for him to find work. For mainstream jazz fans and critics alike, it simply proved far too obtuse. Taylor was viewed as an outsider, a role that brought him press attention, but not much work. The late 60s and early 70s saw Taylor struggling to get club gigs and record dates, as his style of music was largely pushed aside by pop and Motown hits. During this period, he worked as a record salesman, cook, and dishwasher, and eventually began teaching at the University of Wisconsin, Antioch College in Ohio, and Glassboro State College in New Jersey. Virtually all Taylor’s music from 1967 to 1977 was recorded in Europe.

Taylor was elected by the critics to the Down Beat Hall of Fame in 1975. And by the early 1980s, Taylor’s career began to gather momentum once again with the help from releases in Japan and Europe. Taylor was finally starting to get the recognition his artistry deserved. He began to garner critical, if not popular, acclaim, playing for President Jimmy Carter on the White House Lawn, and being awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1973, and then eventually a MacArthur Fellowship in 1991.

Cecil Taylor’s style has often been described by critics as “dense and intense” jazz. Music critics and fans both either loved or loathed his style, but he did have many passionate fans, and among them were his fellow musicians. In 1986, he was honored with a Cecil Taylor Week sponsored by the Berlin Free Jazz Society. All the sessions were released on an eleven-CD box set. Taylor has also been voted the number one pianist in Downbeat Magazine’s International Critics Poll for numerous consecutive years. He was honored with a special Library of Congress concert in Washington, DC in February of 1999.

Taylor recorded sparingly, but continued to perform with his own ensembles (the Cecil Taylor Ensemble and the Cecil Taylor Big Band) as well as with other musicians such as Joe Locke, Max Roach, and the poet Amiri Baraka. In 2004, the Cecil Taylor Big Band at the Iridium 2005 was nominated as best performance by All About Jazz, and the same in 2009 for the Cecil Taylor Trio at the Highline Ballroom. The trio consisted of Taylor, Albey Balgochian, and Jackson Krall.

Taylor also was an accomplished poet, citing Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, and Amiri Baraka as major influences. He often integrated his poems into his musical performances, and they frequently appeared in the liner notes of his albums. Taylor incorporated poetry into his work in a number of ways over the years, including his 1991 recording “Chinampas,” which presents his poetry accompanied by multi-instrumental improvisations.

With almost 30 recorded albums and many more collaborations with other artists, Taylor was a man who commands great respect today, largely because he is seen as an artist who never compromised his creativity. As far back as 1956, the great jazz critic Nat Hentoff (“Downbeat Magazine,” the “Village Voice”), wrote in the liner notes to “Jazz Dance” that “We are in the presence here, and in all [Taylor’s] works, of that rarest of phenomena—a genuine creator. And once you absorb his music you will never quite hear the same again.” As passionate about music as Taylor is, he reportedly never listens to his own stellar recordings. He explains his aversion to his own recordings by stating, “I know what happened.”

In August of 2014, Taylor had a prize sum of nearly half a million dollars stolen from him by a general contractor who befriended him while working next to his house in New York City. Taylor traveled to Japan to collect the prestigious 2013 Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy from Japan’s Inamori Foundation in November of 2013. According to the district attorney’s statement, Noel Muir, a contractor who had worked for Taylor’s neighbor, joined him for the event and helped the musician prepare for the trip. “The defendant befriended Mr. Taylor and won his trust, which later made it easier for him to allegedly swindle this vulnerable, elderly and great jazz musician,” said then-Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson.

In 2014, Taylor’s career and 85th birthday were honored at the Painted Bride Art Center in Philadelphia with the tribute concert event Celebrating Cecil. In 2016, he received a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art entitled Open Plan: Cecil Taylor. Taylor, along with dancer Min Tanaka, was the subject of Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s 2016 documentary film, “The Silent Eye.”

Although publicly outed by critic Stanley Crouch in 1982, Taylor never denied his same-gender attractions. In 1991, Taylor told a “New York Times” reporter, “[s]omeone once asked me if I was gay. I said, ‘Do you think a three-letter word defines the complexity of my humanity?’ I avoid the trap of easy definition.” Although a very public person, Taylor lived a relatively quiet life in his three-story brownstone in the Fort Greene section of Brooklyn, until his death in 2018.

We remember Cecil Taylor for his considerable creative contributions to jazz, and his support of our community.