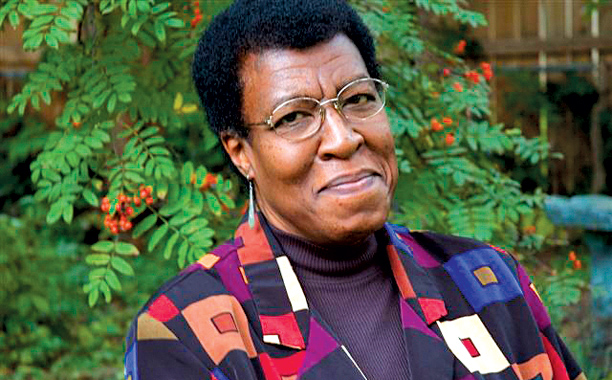

Octavia Butler

[Editor note: Although Octavia Butler never publicly discussed her sexuality, her biography has been reproduced here as written and published by Stephen Maglott (with minor updates), who references the ongoing discussion about how she identified.]

Octavia Butler was born on June 22, 1947 (to February 24, 2006). She was a celebrated American Science Fiction author, who excelled in a genre with few African-American women. She won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. In 1995, she became the first science fiction writer to receive the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant.

Octavia Estelle Butler was born and raised in Pasadena, California. Her father Laurice, died when she was a baby, and Butler was raised by her grandmother and her mother (Octavia M. Butler), who worked as a maid in order to support the family. She grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood. According to the Norton Anthology of African American Literature, Butler was “an introspective, only child in a strict Baptist household” and was drawn early to science fiction magazines such as “Amazing,” “Fantasy,” “Science Fiction,” and “Galaxy,” and soon began reading all the science fiction classics.

Nicknamed “Junie,” Octavia Butler was paralytically shy and a daydreamer, and was later diagnosed as being dyslexic. She began writing at the age of ten “to escape loneliness and boredom,” and when she was twelve, she began her lifelong interest in science fiction.

After earning her associate’s degree from Pasadena City College in 1968, she enrolled at California State University in Los Angeles. She eventually left CalState and took writing classes through a UCLA extension. She would later credit two writing workshops for giving her “the most valuable help I received with my writing.” She participated in The Open Door Workshop of the Screen Writers Guild of America West, a program designed to mentor Latino and African American writers. Through Open Door, she met the noted science fiction writer Harlan Ellison in 1969. She also had high praise for her time in The Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, where she first met Samuel R. Delany. She remained, throughout her career, a self-identified science fiction fan, an insider who rose from within the ranks of the field.

For some writers, science fiction serves as means to delve into fantasy. But for Butler, it largely served as a vehicle to address issues facing humanity. It was this passionate interest in the human experience that imbued her work with a certain depth and complexity. In the mid-1980s, Butler began to receive critical recognition for her work.

Butler won the Nebula Award for Best Novel with “Parable of the Talents” in 1999, the Hugo and Locus Awards for Best Novelette, “Bloodchild” in 1985, and the Hugo Award for Best Short Story for “Speech Sounds” in 1984. In 1995, Butler received a “genius” grant from the MacArthur Foundation, which allowed her to buy a house for her mother and herself. She has been inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

In 1976, Butler published her first novel, “Patternmaster.” This book was the first in a series of works about a group of people with telepathic powers called Patternists. Other Patternist titles include “Mind of My Mind” in 1977 and “Clay’s Ark” in 1984.

In the late 1980s, Butler published her Xenogenesis trilogy—“Dawn” in 1987, “Adulthood Rites” in 1988 and “Imago” in 1989. This series of books explores issues of genetics and race. To insure their mutual survival, humans reproduce with aliens known as the Oankali. Butler received much praise for this trilogy. She went on to write the Parable series, which includes the novels “Parable of the Sower” in 1993, and “Parable of the Talents” in 1999.

In 1999, Butler abandoned her native California to move north to Seattle, Washington. She was a perfectionist with her work and spent several years grappling with writer’s block. Her efforts were hampered by her ill health and the medications she took. After starting and discarding numerous projects, Butler wrote her last novel “Fledgling” in 2005.

In an interview by Randall Kenan, Octavia E. Butler discusses how her life experiences as a child shaped most of her thinking. As a writer, Butler was able to use her writing as a vehicle to critique history under the lenses of feminism. In the interview, she discusses the research that had to be done in order to write her bestselling novel, “Kindred.” Most of it is based on visiting libraries as well as historic landmarks with respect to what she is investigating. Butler admits that she writes science fiction because she does not want her work to be label or used as a marketing tool. She wants the readers to be genuinely interested in her work and the story she provides, but at the same time she fears that people will not read her work because of the “science fiction” label that they have.

The nearly reclusive Octavia Butler died unexpectedly in February of 2006 at her home in Seattle after falling and sustaining a head injury. With her death, the literary world lost one of its great storytellers. She is remembered, as Gregory Hampton wrote in Callaloo, as writer of “stories that blurred the lines of distinction between reality and fantasy.” And through her work, “she revealed universal truths.”

Much has been written about Octavia E. Butler’s sexual orientation Many obituaries recognized her as “both a Black and Lesbian science-fiction writer” All references seem to link to an unsourced Wikipedia post. She has been described by some close friends as bisexual, as asexual, and as heterosexual. She apparently never discussed any lesbianism publicly. There is even a discussion with Octavia Butler and fellow Black sci-fi author Samuel Delaney on the MIT website where he briefly talks about being a gay man. It would seem natural that Octavia Butler might have used the opportunity to acknowledge that she was a lesbian, but she did not mention it in that discussion. Dr. Ron Buckmire, a math professor at Occidental College, very near where Miss Butler lived until her move to Seattle, writes in his blog his reflections on her passing. He says that he knew her casually and does remark that she was a lesbian. Whatever her orientation, she was a gifted and inspiring writer whose work impacted and inspired the lives of many.

The Octavia E. Butler Memorial Scholarship was established in Butler’s memory in 2006 by the Carl Brandon Society. Its goal is to provide an annual scholarship to enable writers of color to attend one of the Clarion writing workshops where Butler got her start. The first scholarships were awarded in 2007.

In April 2014, it was announced that two new stories by Octavia E. Butler had been discovered among her papers at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California; her work continues to be published and adapted today.

We remember Octavia E. Butler in appreciation for her brilliant writing, her unique and pioneering spirit, and for her many contributions to our community.