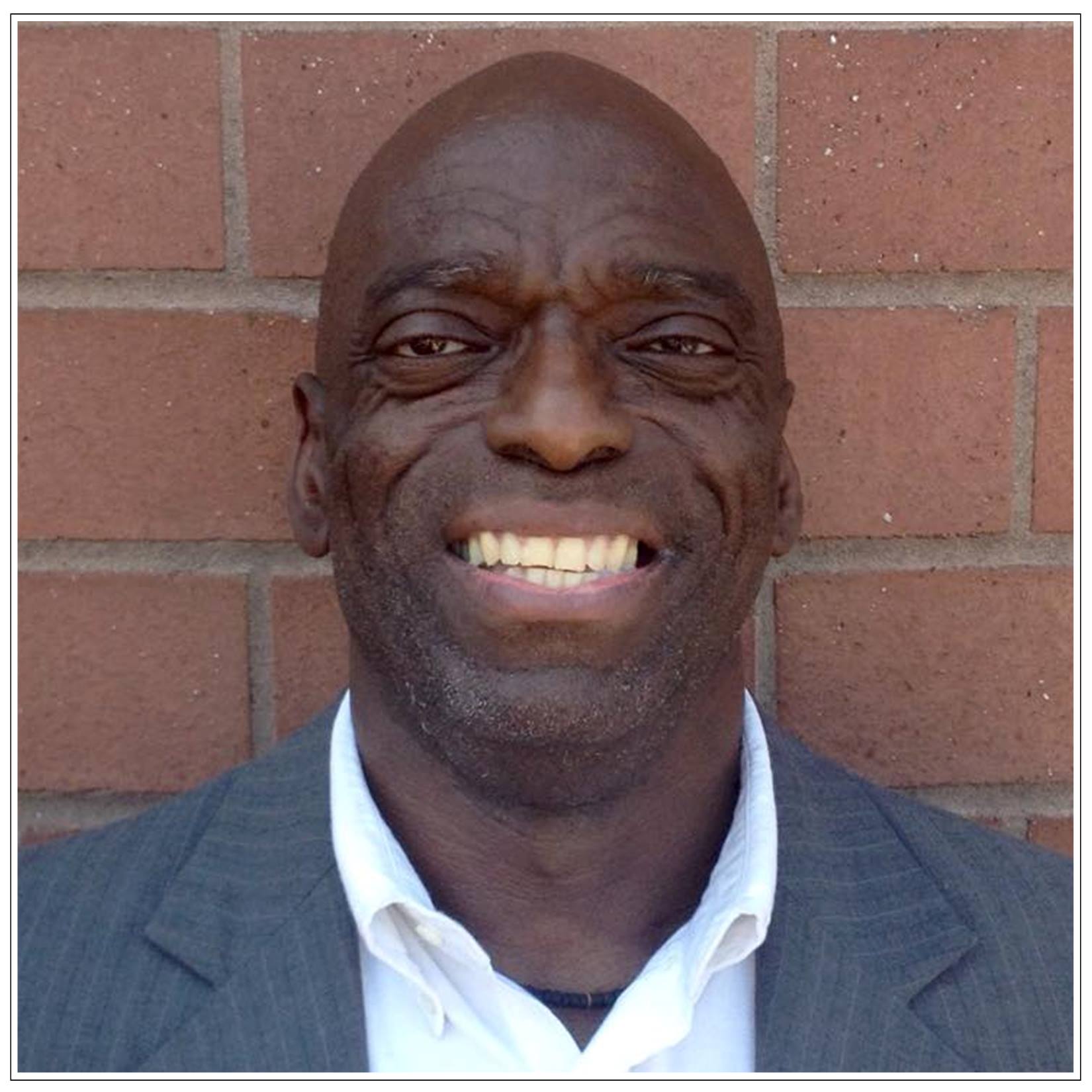

Dr. John Young

John Young was born July 14, 1962. He is a scholar, educator, historian, advocate, activist, concert pianist, and a good friend.

Dr. John Young, known to many of his friends as Martey Beku, was born in Amityville, New York, to John and Clothilde Young. He has one older brother and is a graduate of Copiague Senior High School. With a passion for television growing up, John loved to watch human-interest stories about other young people. After seeing several programs dedicated to gifted and talented children, he noticed they always seemed to feature Asian or Jewish kids playing either the violin or piano with big orchestras; Black children were never seen doing the same thing. Consequently, at the age of ten, John made a conscious decision to be the first African American male concert pianist.

John not only began to spend hours practicing the piano, he also decided to become a top academic student as well, doubling and sometimes tripling time spent on homework and studying. Also, after seeing too many adult Black men in his neighborhood not doing anything with their lives, his desire to make something of his life and to leave his mark on this world continued to grow.

Pursuing his goal at an early age created problems with his peers. Starting in sixth grade, being academically oriented and taking homework and studying seriously in middle school did not endear him to his classmates, particularly African American boys. Assuming a favorable stance to learning, doing well in school, and not having much interest in team sports was a social death sentence for him as a ten-year-old. From playing with other boys around the block to constantly reading, studying and practicing, John learned the consequences of wanting to be a smart Black boy early on. Isolation and loneliness soon became commonplace, and not having other African American boys with whom to share his love of learning, school, classical music, appreciation for the arts, and church made him a pariah among his peers.

Despite this social impediment, John persevered and achieved well enough academically to be placed in honors and Advanced Placement (AP) classes in high school. It was in those classes that he was faced with another but different peer relationship challenge. Being the only Black male in those courses was burdensome because few, if any, of the white students in the same honors or AP classes would talk to him, let alone work with him. However, the love and support of his parents and church family played a decisive role in encouraging his voracity to be somebody. Both of John’s parents were born and raised in the Deep South during the Depression at the pinnacle of Jim Crow segregation, and they would recite stories about growing up in that era. From those tales of horror, John learned to exploit every opportunity available to him and make the most of his education in spite of what others thought. Eventually, he graduated eighth in his class out of 416 students, and was named a National Achievement Commended Scholar and a New York State Regents Scholar.

After graduating from high school, John enrolled as a double degree student at Oberlin College and its Conservatory of Music, majoring in both piano performance and mathematics. The vault from a working class, public high school to a top, nationally ranked, elite liberal arts college was extremely traumatic—so much so that he discontinued the piano major after his first year. No longer having to practice five to six hours nearly every day of the week, John began to discover who he was as a person. He learned techniques of activism through Abusua, Oberlin College’s Black student union, volunteered at a local senior citizen’s home, and started an afterschool tutoring program for the children of the African American service workers of Oberlin. This was also the time that John became aware of his sexuality.

At Oberlin, he was the very first person to arrive at African Heritage House his first year. While walking around outside the dorm, he met an older man who introduced himself as Thurlow Tibbs, an urban planner who lived in Washington, DC and was taking care of some legal issues regarding his aunt’s house. Thurlow was the son of the great Black opera star, Madame Lillian Evanti, and the renowned Howard University music professor, Dr. Evans Tibbs. He also was an art broker whose clients were famous African American visual artists. John and Thurlow exchanged addresses, and thus began a pen pal relationship that would later play an important role in his life.

During high school, John never dated under the guise of being too busy, but now he realized that he was attracted to Black men. After a year of corresponding with Thurlow, John decided to visit him in DC during his sophomore spring break. When he arrived at Thurlow’s beautiful brownstone, he was met by a series of handsome men. After the third man introduced himself, John realized that Thurlow was Same Gender Loving (SGL), and it was at that precise moment that John realized he was as well. All those years of not feeling comfortable around females sexually, and all those years of avoiding dating girls suddenly made sense. Thurlow listened to John’s revelation and offered comforting words. When John went back to campus, he struck up a friendship with a well-known, openly SGL male student that, over time, blossomed into a brief romance. Being a Black SGL young man at a small, predominately white college in an even smaller town did not open up many opportunities for John to explore his newly found sexual identity. So, after graduating Oberlin, he enrolled in a Master’s program at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Since Atlanta had recently become a mecca for African American SGL men, John could receive a top-quality graduate education, learn about Black SGL culture, and possibly fall in love. Unfortunately, this new chapter in his life did not turn out completely the way he anticipated. Being 21, not knowing anyone, and being naive about life in general and SGL life in particular, John did what so many young Black men do: he went to the club to find love. Without an older SGL man to mentor, guide, and help him negotiate the Atlanta Black homo world, John fell prey to exploiters. He did manage to graduate with a Master’s of Arts degree in teaching and was exposed to SGL culture of the mid-80s, but love was to escape him, and the dawning of a more pernicious health crisis that was affecting white gay men was lurking in the shadows.

Taking advantage of an offer to commence a doctoral program at Howard University immediately after earning his degree, John moved to Washington, DC. Not long after arriving there, he was able to secure a teaching position with the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) as a high school math teacher and take classes at Howard University. Teaching in DC was both rewarding and frustrating for him. Even though he was able to positively influence some students, too many other students had urgent life issues that needed immediate attention, beyond the scope of a teacher’s ability to help. John was named a finalist in the National Teacher of the Year Program for the DCPS, an Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellow, a Princeton University Woodrow Wilson Education Fellow, and was nominated for the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics Teaching. Outside of becoming a recognized and award-winning teacher, John became interested in fitness, eventually became a certified fitness trainer and taking up bodybuilding.

That aforementioned health crisis that was affecting white gay men was starting to impact primarily SLG men. Consequently, the activism skills he learned at Oberlin became useful in aiding organizations in the District of Columbia to combat the impending HIV/AIDS pandemic affecting and afflicting SGL Black men. John used his newly acquired fitness expertise by offering fitness classes to interested community members at the long-defunct ICAN and Us Helping Us, both HIV/AIDS service organizations. It wasn’t until several years after his involvement with these organizations that he learned that he had contracted HIV. The revelation devastated him because he thought he was going to die the next day (this was 1988). John subsequently found love several times, and learned that there are Black men who love other Black men despite their HIV status.

Leaving DC was a difficult decision for John to make, but since his father had made his transition, his beloved mother was living alone, had taken ill, and needed assistance. With his help, John’s mother recovered and became well enough to live alone again. He moved to New York City, where he transferred the community activism and advocacy skills refined in DC and volunteered at Gay Men of African Descent, People of Color in Crisis, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Adodi New York, Black Men’s Exchange, and several other community-based organizations. For over a decade, John devoted his time and energy toward the fight for justice for African American people in general, and African American SGL men in particular. In recognition of his dedication to serving the African American community, John received the Out Standing Man Award, was inducted into the inaugural Hall of Achievement of Copiague Public Schools, and named an Outstanding Young Man of America.

His passion for education and ministry to teach replaced his AIDS activism during the turn of the 21st century. Being accepted into the doctoral program in gifted education at Columbia University Teachers College, John turned his attention toward becoming a scholar. For eight years he went to class, worked part-time, volunteered, and was involved with fitness. Eventually, John became the first male in the history of Columbia University Teachers College to earn a doctorate in gifted education, winning a Spencer Foundation Research Training Grant, the Lydia Donaldson Tutt-Jones Memorial Research Grant, the Betty Fairfax Professional Development Grant, the President’s Grant for Research in Diversity, the Glickstein Prize. He was also named an Audre Lorde Scholar.

Today, John owns an educational consulting firm that provides study skill assistance to middle and high school students; guides parents and students in the selective public and private high school selection process; provides college selection counseling; and offers parent workshops addressing how they can be effective at maximizing their child’s learning environment. John is most proud of a workshop he conducts entitled, “A Father’s Role in His Child’s Education.” Despite health challenges, he is making a difference in the lives of African American SGL men and women in New York City.

John believes that God empowers individuals to be open and honest, to inspire others, and make the planet a better place. He is single, has an adult surrogate son, mentors several Black men and woman, loves fitness and bodybuilding, and enjoys the performing arts, reading, community service, socializing, “healthy” soul food, Italian, Asian and French cuisine, and tries to live a healthy lifestyle. He welcomes inquiries and messages, and can be reached at 347-310-1794.

We thank Dr. John Young for his decades of advocacy, and for his unwavering support of our community.