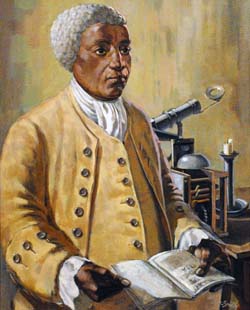

Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker was born on November 9, 1731 (to October 9, 1806). He was an important Colonial American scientist, mathematician, astronomer, inventor, and publisher.

Benjamin Banneker was born in Baltimore County, Maryland to Mary Banneky, the biracial daughter of Molly Welsh and her former slave, Banneka. Little is known about Benjamin’s father, Robert, a first generation slave who had fled his owner. There are plenty of inconsistencies in the history of Benjamin Banneker, and many of these involve his ancestry. His maternal grandmother, said to be Molly Welsh, was a white Englishwoman who came to the United States, purchased two slaves, and then liberated and married one of them, a man named Banneka, whom she purchased to help establish a farm located near the future site of Ellicott’s Mills. Their daughter, who also married a slave, was Banneker’s mother. None of Banneker’s surviving papers describe a white ancestor or identify the name of his grandmother. The first published description of Molly Welsh as having come from Europe was based on interviews with Molly’s descendants that took place during and after 1836, long after the deaths of both Molly and Benjamin.

From a very young age, Banneker was taught reading and religion by his grandmother. He met and befriended Peter Heinrichs, a Quaker farmer who established a school near Banneker’s family farm. Heinrichs shared his personal library with Banneker, and provided his only known classroom instruction. Quakers were leaders in the anti-slavery movement, and advocates of racial equality in accordance with their “Testimony of Equality” belief. Banneker was, however, largely self-taught, and showed a great propensity for mathematics and an astounding mechanical ability. Later, he was forced to leave school to work the family farm, but he continued to be an avid reader. Banneker spent the majority of his life at that farm, and was named on the deed in 1737.

Although he had no previous training, Benjamin Banneker used a pocket watch he had borrowed as a model, and carved wooden replicas of each piece to create a clock that struck hourly. He completed the clock in 1753, at the age of 22, and that timepiece continued to work until his death.

In 1771, a white Quaker family, the Ellicotts, moved into the area and built mills along the Patapsco River. Banneker supplied their workers with food, and studied the mills. In 1788, he began his more formal study of astronomy, using books and equipment that George Ellicott lent to him. The following year, Banneker sent George Ellicott his work on a solar eclipse. In February 1791, Major Andrew Ellicott, a member of the same family, hired Banneker to assist in the initial survey of the boundaries of the 100-square-mile federal district (today known as the District of Columbia) that Maryland and Virginia would cede to the federal government for the establishment of the nation’s capital.

Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey the area at the age of 59, Banneker left the boundary survey in April 1791, and returned to his home at Ellicott’s Mills to work on an ephemeris. Banneker made astronomical calculations that predicted solar and lunar eclipses, and those calculations were included in a six-year series of almanacs, “Almanack and Ephemeris,” which were printed and sold in six cities in four states from 1792 to 1797. He also kept a series of journals that contained his notebooks for astronomical observations and his diary. The notebooks additionally contained a number of mathematical calculations and puzzles.

James McHenry, a signer of the 1787 United States Constitution and self-described friend of Banneker, wrote a preface to the almanac, and they were heavily promoted by the Society for the Promotion of the Abolition of Slavery of Maryland and of Pennsylvania. William Wilberforce and other prominent abolitionists praised Banneker and his works in the House of Commons of Great Britain.

Benjamin Banneker expressed his views on slavery and racial equality in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, and in other documents that he placed within his 1793 almanac. The almanac contained copies of his correspondence with Jefferson, poetry by the African American poet Phillis Wheatley, and by the English anti-slavery poet William Cowper, as well as anti-slavery speeches and essays from both England and America.

In the letter, Banneker accused Jefferson of criminally using fraud and violence to oppress his slaves by stating, “Sir, how pitiable is it to reflect, that although you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of Mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of these rights and privileges, which he hath conferred upon them, that you should at the same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren, under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the same time be found guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.”

Because of declining sales, Banneker’s last almanac was published in 1797. After selling much of his farm to the Ellicotts and others, he died in his log cabin nine years later on October 9, 1806, just before his 75th birthday. His chronic alcoholism, which worsened as he aged, may have contributed to his death. A commemorative obelisk that the Maryland Bicentennial Commission and the State Commission on Afro American History and Culture erected in 1977 stands near his unmarked grave in an Oella, Maryland, churchyard. In 1980, the U.S. Post Office issued a Black Heritage commemorative stamp in his honor.

Benjamin Banneker never married, and is not known to have had any liaisons with women. In one of his early essays, he stated that poverty, disease, and violence are more tolerable than the “pungent stings…which guilty passions dart into the heart,” prompting some historians to view him as most probably homosexual. According to “Gay & Lesbian Biography,” Banneker’s “self-isolation and love of drink is sometimes cited as at least a partial explanation for his lifelong bachelorhood. But his grandmother, parents, and sisters were known to be people of considerable Christian dominance, and he always lived under their supervision.” Banneker, whose name is included on The Blacklist, lived in an era when discussions of intimacy were forbidden and considered sinful. Also, as he grew older, Banneker regularly read the Bible, the teachings of which may have helped quash any same-gender passions.

We remember Benjamin Banneker in appreciation of his brilliant and enduring contributions to our community.