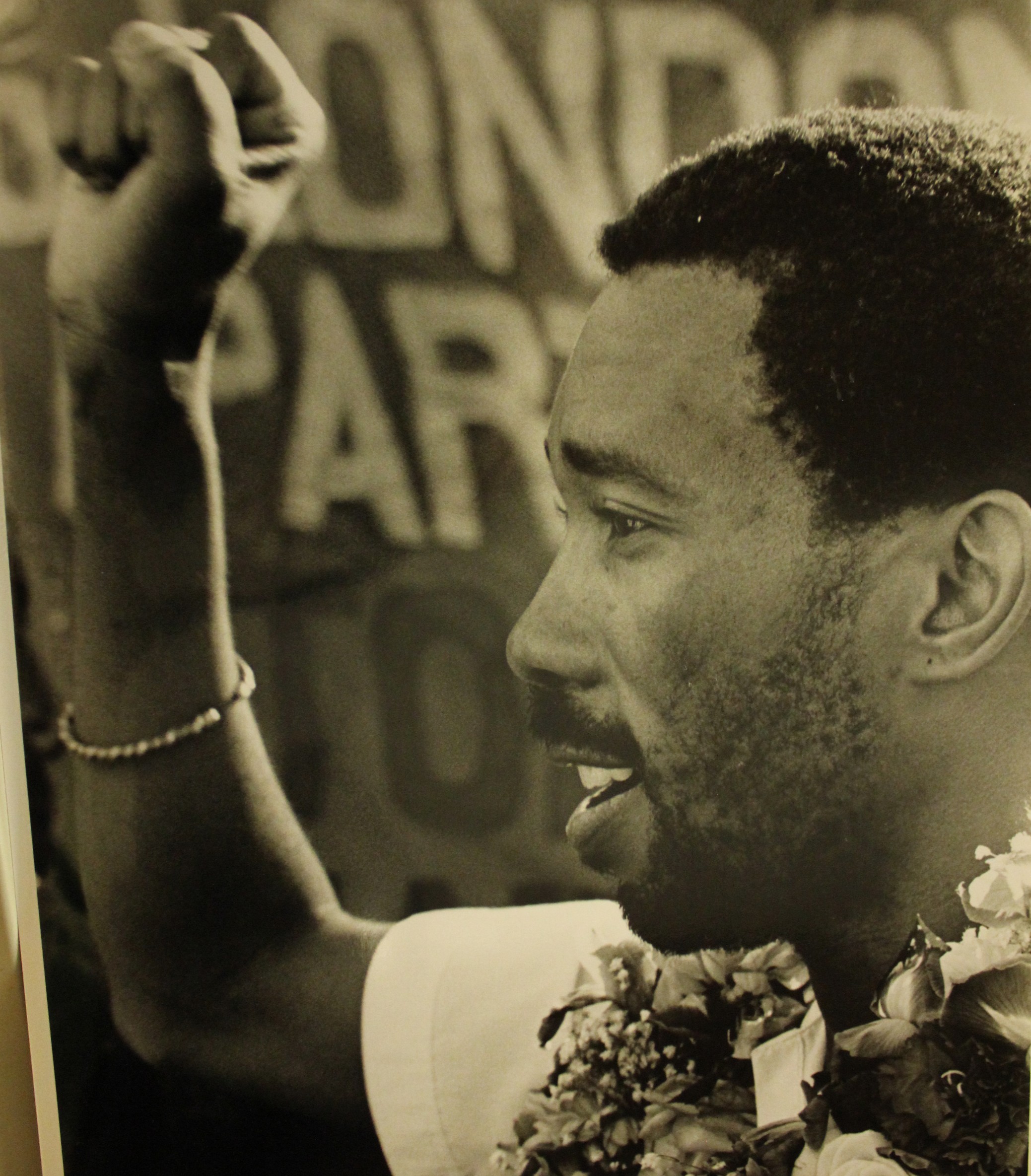

Simon Tseko Nkoli

Simon Tseko Nkoli was born on November 26, 1957 (to November 30, 1998). He was an important anti-apartheid, gay rights, and AIDS activist in South Africa.

Simon Tseko Nkoli was born in Soweto, South Africa in a seSotho-speaking family. He grew up on a farm in the Free State, and his family later moved to Bophelong Township, near Sebokeng. South Africa’s apartheid laws imposed severe limitations on his family’s opportunities. Nkoli told the story of how, at age nine, he locked his parents in a wardrobe so they could escape detection from police enforcing the pass laws, which restricted where Black residents could live. That experience left a powerful impression that he used later as a metaphor for living a closeted life.

Nkoli spent much of his childhood with his grandparents, low-income tenant farmers on a white-owned estate. He craved education and, against the resistance of the landowner and his grandfather who needed his labor, stole away when he could to attend the rural schools. Eventually, Nkoli rejoined his mother and stepfather in Sebokeng to continue his education.

Simon Tseko Nkoli recognized his feelings for other men while a teenager. Identifying as a gay man was confusing because the seSotho word for homosexual is “sitabane,” which implies hermaphrodite. At 18, Nkoli came out to his mother, who took him to a priest and a series of local healers or “sangomas” who attempted, unsuccessfully, to argue him out of it. At 19, he met his first lover, a white bus driver named Andre, through a pen pal magazine.

The mothers of both young men opposed the relationship—Simon’s because it was gay and Andre’s because it was biracial. Nkoli’s mother arranged for him to see a psychologist, who turned out to be gay and assured him of his rationality. Matters came to a head when the lovers made a suicide pact; Nkoli’s mother learned of it and intervened. The pair were able to live together once they became college students in Johannesburg. Even then, however, to conform to enforced segregation, Nkoli had to pose as Andre’s domestic worker.

After the 1976 Soweto youth uprising, Nkoli became an activist against apartheid. His anti-apartheid activism began when he was arrested four times in the student rebellions. In 1979, he joined the Congress of South African Students (COSAS), and became secretary for the Transvaal region. When Nkoli’s homosexuality became known, it was debated among his fellows within the organization; they voted to retain him in the post.

After Nkoli’s first relationship ended, he found few resources for gay people of color. Most gay venues, except a few cruising areas, were in districts reserved for whites. In 1983, his allegiances in racial and sexual identity politics intersected: he came out in an interview in the “City Press,” a Black newspaper, and joined the virtually all-white Gay Association of South Africa (GASA), which maintained an apolitical distance from the apartheid struggle. Receiving little support within GASA for advocating that they relocate their social activities away from whites-only facilities, in May of 1984 Nkoli started The Saturday Group, South Africa’s first gay Black organization. It was short-lived, however, because Nkoli’s political life soon took a dramatic turn.

In the 1980s, Nkoli’s student activism resulted in his joining the African National Congress and the United Democratic Front (UDF). In 1984, he helped establish the Vaal Civic Association to undertake tenant organizing in the Delmas township. Nkoli and 21 others from the UDF were arrested after a march protesting government-imposed rent hikes, and charged with “subversion, conspiracy, and treason,” crimes subject to the death penalty.

The “Delmas Trial” lasted four years. While in the Pretoria Central Prison, Nkoli came out to his comrades during discussions of prison sex. This action and the debates it inspired prompted UDF leaders such as co-defendants Popo Molefe and Patrick Lekota to recognize homophobia as a form of oppression, and embrace Nkoli and his struggles as theirs.

During the trial, Nkoli’s substantiation of his attendance at a GASA meeting was a crucial point in countering the prosecution, which had tried to place him at the scene of a murder. The defense was also a public coming out, and brought the Delmas Trial to the attention of the international gay rights movement. The letters of support he received, especially from European activists, were an important demonstration of solidarity. Nkoli was acquitted in 1988, and he and the rest of the “Vaal 22” were freed. However, during his imprisonment, Nkoli learned that he was HIV positive.

Ironically, GASA had withheld its support during the trial. Discerning a need, upon his release Nkoli helped found the Gay and Lesbian Organization of Witwatersrand (GLOW), the first large Black-based SGL/LGBT organization in South Africa. Beginning in 1990, GLOW organized the country’s first three pride marches, and became the model for several other gay groups in the Black townships.

Nkoli continued his participation in the ANC, meeting with Nelson Mandela in 1994. His visibility in the anti-apartheid movement merits much of the credit in winning the ANC’s support for gay rights—support that translated into tangible deeds once the ANC gained power. In 1996, South Africa became the first nation to include sexual orientation in its constitution’s anti-discrimination clause. This milestone victory for equality is the fountainhead from which many other gains for South African SGL/LGBT people flow, including the invalidation of sodomy laws, and the recognition of gay relationships.

In 1990, Nkoli became one of the first South African activists to publicly acknowledge his HIV-positive status. He co-founded the Township AIDS Project (TAP) and the Gay Men’s Health Forum, working diligently to bring AIDS education and counseling to disadvantaged populations. He was also a founding member of both the Positive African Men’s Project and the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality (now the Lesbian and Gay Equality Project), as well as a board member of the International Lesbian and Gay Association, representing the African region. Playful and irreverent, Nkoli inspired the devotion of South African progressives from all backgrounds and drew an international following. A 1989 speaking tour of Europe, Canada, and the United States raised $35,000 for TAP.

Nkoli had been infected with HIV for around 12 years, and had been seriously ill, on and off, for the last four. He lost his struggle against the virus in a Johannesburg hospital on November 30, 1998, just days after his 41st birthday. He lived to see the rights of lesbian and gay people enshrined in the Constitution and in the protected freedoms of South Africa, and he played an important role in that achievement.

A memorial at St. Mary’s Anglican Cathedral was followed by a funeral in Sebokeng attended by many of the SGL/LGBT and anti-apartheid movements’ luminaries. The September 1999 Johannesburg Pride march was dedicated to Nkoli, and included a stop at the newly named Simon Nkoli Corner at the intersection of Pretoria and Twist Streets in Johannesburg.

Nkoli’s papers at the Gay and Lesbian Archives of South Africa include his letters from prison, which were the basis for Canadian filmmaker John Greyson’s 1987 short film about Nkoli, “A Moffie Called Simon. Nkoli was the subject of Robert Colman’s 2003 play, “Your Loving Simon,” and Beverley Ditsie’s 2002 film, “Simon & I.” John Greyson’s 2009 film, “Fig Trees,” a hybrid documentary/opera includes references to Nkoli’s activism. There is a Simon Nkoli Street in Amsterdam, and a Simon Nkoli Day in San Francisco. Nkoli opened the first Gay Games in New York, and was made a freeman of that city by New York City Mayor David Dinkins. In 1996, Nkoli was given the Stonewall Award in the Royal Albert Hall in London.

We remember Simon Tseko Nkoli in recognition of his contributions to the struggle for freedom and justice, for his remarkable life, for his inspiring courage and determination, and for his many contributions to South Africa and our community.