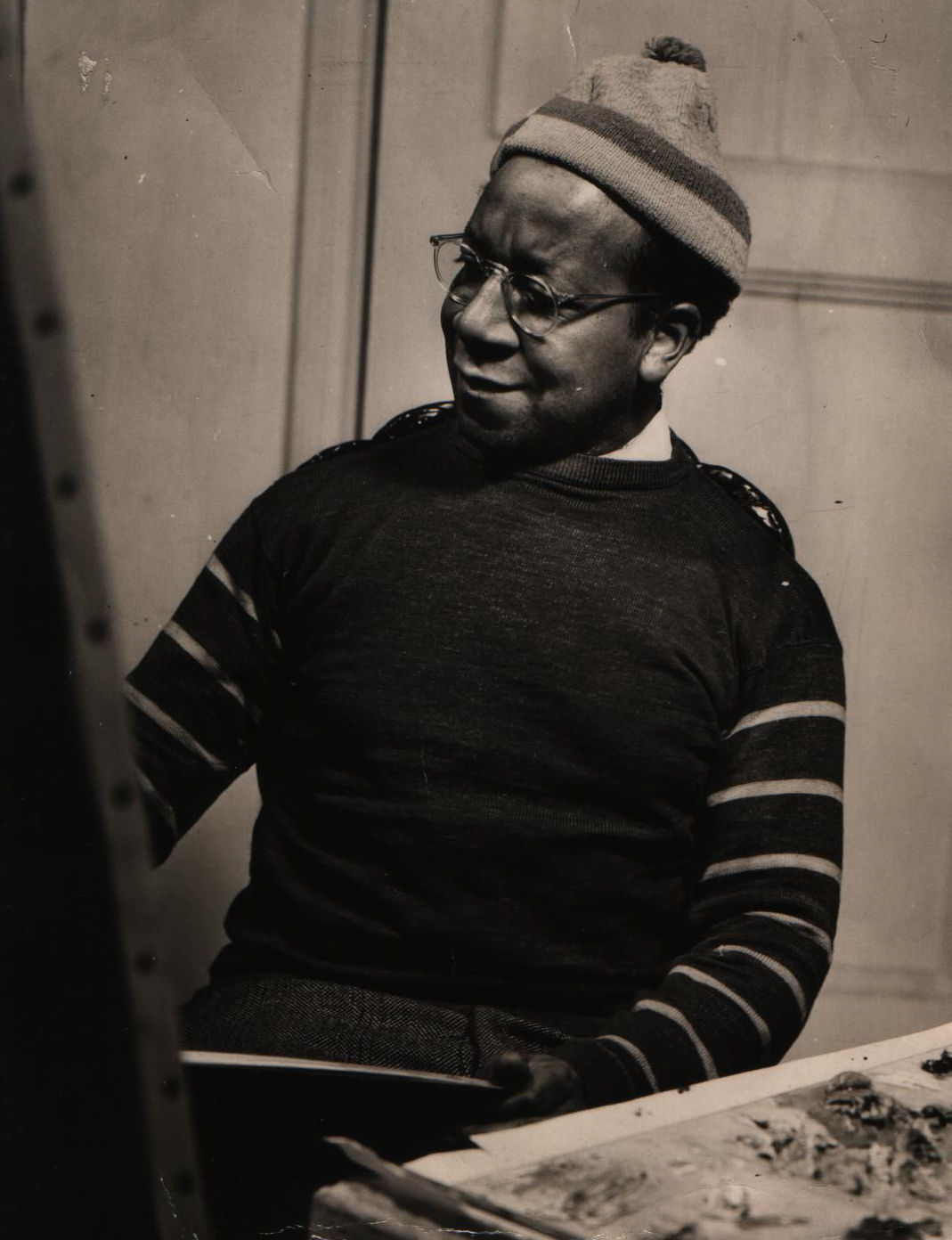

Beauford Delaney

Beauford Delaney was born on December 30, 1901 (to March 26, 1979). He was an important modernist painter remembered for his work during the Harlem Renaissance, as well as his later works in abstract expressionism following his move to Paris, France, in the 1950s.

Beauford Delaney was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, the son of respected members of Knoxville’s Black community. His father, Samuel, was a barber and a Methodist minister, and his mother, Delia, was prominent in the church, and earned a living taking in laundry and cleaning the houses of local white residents. Delia was born into slavery and never taught to read or write. But she instilled in her children a sense of dignity and self-esteem, and preached to them about the injustices of racism, and the value of education. Beauford was the eighth of ten children, many of whom died in infancy, with only four surviving into adulthood.

Beauford’s younger brother, Joseph, was also a noted painter, and both were attracted to art from an early age. Some of their earliest drawings were copies of Sunday school cards, and pictures from the family bible. They were constantly doing something with their hands—modelling with the red Tennessee clay, and copying pictures. Beauford Delaney also had musical talents, and loved to sing and play a ukulele.

When he was a teenager, Delany worked at a sign company, and his work was noticed by Lloyd Branson, an elderly American Impressionist, and Knoxville’s best-known artist. By the early 1920s, Delaney became the apprentice of Branson, and with his encouragement, the 23-year-old Delaney migrated north to Boston, Massachusetts to study art. He had arrived with letters of introduction in hand, and was invited into the parlors of Boston’s upper-class society of social activists. He received what he referred to as a “crash course” in Black activist politics and ideas, having associated socially during his years in Boston with some of the most sophisticated and prominent Black thinkers of the time, including writer, diplomat, and rights activist James Weldon Johnson; William Monroe Trotter, founder of the National Equal Rights League; and Butler Wilson, a board member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACO).

With perseverance, Delaney learned what he called the “essentials” of classical technique, and achieved the artist’s education he desired—including informal studies in 1924 at the Massachusetts Normal School, the South Boston School of Art, and the Copley Society—under the tutelage of Thomas Hart Benton, John Sloan, and Don Freeman. He was also influenced by a local painter, Alfred Morang, whose broad strokes were compared to those of Van Gogh. Delaney stood out as an African American moving through Boston’s white society, and he struggled with the many intersections of his identity. But he was soon to add another.

It was while in Boston that Delaney had his first “intimate experience” with a young man in the Public Garden. He would reveal little about his passions and love over the course of his lifetime, and frequently hid his sexual orientation, fearful of conflict and condemnation from others. By 1929, the essentials of his artistic education complete, Beauford decided to leave Boston and head for the creative metropolis of New York City.

Beauford Delany arrived in Harlem during the Renaissance, and at the start of the Great Depression. He was resourceful and created work for himself by offering to draw portraits of the city’s elite. The quality of his portraiture garnered him a position as a sketch artist at a dance school. One of his portraits was published in the “New York Telegraph” and the “Chicago Defender.” The exposure led to his work being exhibited in 1930 at the Whitney Studio Galleries, which later became the Whitney Museum of American Art. Delaney’s exhibition received positive reviews, and he continued to paint New York socialites, Black leaders, jazz musicians, and the people of Harlem.

In 1932, Delaney’s paintings were exhibited at the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue. Now a full-time artist and teacher, he joined the Art Students’ League, and became a member of the Harlem Arts Guild. Much of his work of this period was of Black subjects, and New York’s Black community. For Delaney, art was primarily expression rather than commentary. Although he was very much in tune with the issues of the day, his style became more abstract as an expression of his inner world. Delaney also found inspiration in jazz, and created works that were similarly complicated, unpredictable, and escaped traditional form. He quickly gained wide recognition for his pastel portraits of well-known African Americans such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Duke Ellington.

Harlem was very much in vogue, and the center of Black cultural life in the United States. But it was also the time of the Great Depression, and Beauford Delaney experienced some lean times. He wrote, “Went to New York in 1929 from Boston all alone with very little money…this was the depression, and I soon discovered that most of these people were people out of work and just doing what I was doing—sitting and figuring out what to do for food and a place to sleep.”

Delaney felt an immediate affinity with this “multitude of people of all races—spending every night of their lives in parks and cafes” surviving on next to nothing. The tough times and those enduring them with dignity became the subjects of many of Delaney’s greatest New York period paintings. He painted colorful, engaging canvasses that captured scenes of the urban landscape. His works express not only the character of the city, but also his personal vision of equality, love, and respect among all people.

But quixotic portraits were only part of Delaney’s interests. He captured African American influences, such as jazz clubs and street life of Harlem in his artwork. His modernist cityscape “Greene Street” was compared to artists such as Van Gogh and Cézanne. He completed “Can Fire in the Park” in 1946, which features a group of men huddled together for warmth and companionship around an open fire. The impressionist masterpiece is described by the Smithsonian American Art Museum as conveying “a legacy of deprivation linked not only to the Depression…but also to the longstanding disenfranchisement of Black Americans.” At the lower left and upper right, objects that suggest street signs also function as arrows symbolically pointing the way up and out of desolation.

Having received greater recognition, Delaney was featured in the exhibit, “The Negro in Contemporary Art,” where his “Othello” was well received. His 1948 solo exhibit at the Artist’s Gallery brought acceptance of Delaney as one of New York’s most important expressionists. As an artist he was adored, but as a Black artist, he was rarely celebrated.

Life was far from lush for Beauford Delaney, who was forced to seek a consistent income source, eventually obtaining work as a bellhop, and later as a telephone operator, doorman, caretaker, and janitor. He also managed to find, as he wrote later, “little corners in the world of the Great Depression that would or could be receptive to his work.” In time, his talent and brilliance became part of the bohemianism of the era’s vibrant art scene. His friends included the poet laureate Countee Cullen, writer James Baldwin, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, writer Henry Miller, and many others.

Despite the friendships and successes of this period, Delaney remained a rather isolated individual amid New York’s millions of people. In his 1998 biography “Amazing Grace: a life of Beauford Delaney,” David Leeming presents Delaney as having led a very “compartmentalized” life. In New York’s Greenwich Village, where his studio was located, Delaney became part of a gay bohemian circle of mainly white friends; but he was furtive and rarely comfortable with his sexuality. In the Village, he found freedom to explore a conflicted gay life. To a lesser extent, he was also conflicted about Harlem, and often sought to distance himself from Manhattan’s most famous neighborhood. When he traveled to Harlem, he made efforts to ensure that his African American friends and colleagues knew little of his downtown life. Delaney feared that many of his Harlem friends would be uncomfortable or repelled by his homosexuality, and he feared their rejection.

The pressures of being Black and gay in a racist and homophobic society would have been difficult enough, but Delaney’s own Christian upbringing and “disapproval” of homosexuality weighed heavily on him. The presence of his artist brother Joseph in the New York art scene and the “macho abstract expressionists emerging in lower Manhattan’s art scene” added to this pressure. So, he remained isolated as an artist, even as he worked in a center of artistic achievement. A deeply introverted and private person, Delaney appeared to form no lasting romantic relationships.

Although he resisted thinking of himself as a “Negro” artist, Beauford had tremendous pride in Black achievement. He was also pleased to participate in several Black artist exhibitions with fellow artists Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff, Selma Burke, Richmond Barthé, Norman Lewis, and his brother, Joseph Delaney. Beauford’s work earned him the coveted Exhibition Prize from the Village Art Center in 1948, but it did not appear to enrich his life monetarily, as it had for legions of prominent white artists.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum notes that “neither early success nor gracious spirit spared Delaney from the obscurity and poverty” that plagued him most of his adult life. Brooks Atkinson wrote in his 1951 book “Once Around the Sun,” “No one knows exactly how Beauford lives. Pegging away at a style of painting that few people understand or appreciate, he has disciplined himself, not only physically but spiritually, to live with a kind of personal magnetism in a barren world.” Some critics have suggested that his paintings speak of his own suffering, but in a way that celebrated that and many other experiences. His work was said to be never depressing, though Beauford himself was often depressed. He could say yes to life despite the fact that life was doing its best to beat him down.

Delaney was awarded a brief fellowship at Yaddo, an artists’ retreat in upstate New York. The time spent outside of the city in nature settings moved his work more toward the abstract. His best work of the civil rights era, “Earth Mother,” juxtaposed a European expressionist style with Black objects. His time at Yaddo and away from New York also stimulated thoughts of traveling to Paris.

In 1953, at the age of 52, just as the heart of the art world was shifting to New York, Delaney left for Paris. Europe had already attracted many other African American artists and writers who had found a greater sense of freedom there. Writers Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Chester Himes, Ralph Ellison, William Gardner Smith, and Richard Gibson, and artists Harold Cousins, Herbert Gentry, and Ed Clark had all preceded him in journeying to Europe. In his journal, Richard Wright described Paris as “a place where one could claim one’s soul.”

Europe would be Delaney’s home for the remainder of his life. His years in Paris would lead to a dramatic stylistic shift from the “figurative compositions of New York life to abstract expressionist studies of color and light.” He adapted a style that became a forerunner of Abstract Expressionists, and as they began to gain notoriety in the late 1940s, Delaney’s abstract work increasingly gained attention. He also continued to create figurative portraits, including one of James Baldwin in 1963 that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. The portrait was said to be “both a likeness based on memory and a study in light.”

Delaney’s mental health deteriorated greatly as he struggled with poverty and conflicts over his sexuality. Hearing of his mother’s death in 1958 added to his depression. Although he found relief in his work, the inner voices and thoughts that had plagued Delaneyfor much of his life returned in full force on a trip to Greece. He is reported to have gone overboard from a ship to escape men whom he believed were trying to kill him. Delaney was diagnosed as having acute paranoid delusions, and was placed on antidepressant medication. With improved health, he returned to his life as a painter in a new studio, acquired for him by friends.

By 1961, heavy drinking had begun to impair Delaney’s often fragile mental and physical health. Continued poverty, hunger, and alcohol abuse fueled his deterioration. James Baldwin observed in 1963, “He has been starving and working all of his life—in Tennessee, in Boston, in New York, and now in Paris. He has been menaced more than any other man I know by his social circumstances and also by all the emotional and psychological stratagems he has been forced to use to survive; and, more than any other man I know, he has transcended both the inner and outer darkness.”

Baldwin and other friends attempted to orchestrate a New York show of his work, to be sponsored by the Urban League. Baldwin’s letter to potential supporters stated that Delaney “brings great light out of the darkness of his journey, and makes his journey and his endeavor, and his triumph ours.” Unfortunately, the show never took place. He received a Fairfield Foundation grant and held a one-man show in 1964; he was now combining portraiture with expressionism. Another Baldwin portrait, this time in 1966, placed dark lines against a yellow abstraction, reflecting Delaney’s departure from representational portraiture. In 1968, Delaney received a grant from the National Council of the Arts, which helped him to continue working. In the early 1970’s, he received many accolades and increased visibility of his work in the States. When praised for this, he commented, “I ain’t seen no famous money, and I’m hungry.”

In 1969, Delaney returned briefly to the United States to see his family, but was dogged by mental illness. He believed malicious people would come to him at night “and speak unpleasant and vulgar language and threaten malicious treatment…interfering with my health and urgent work…the constant, continuous creation.”

He returned to his work in Paris in January of 1970. Shortly thereafter, it became clear that he could no longer cope with daily life. In the autumn of 1973, his friend, Charley Boggs, wrote to James Baldwin, “Our blessed Beauford is rapidly losing mental control.” His friends tried to care for him but, in 1975, Delaney was diagnosed with what was likely Alzheimer’s, and was committed to Saint Anne’s hospital. Beauford Delaney died in Paris, at Saint Anne’s, on March 26, 1979. He was interred at the Parisian Cemetery of Thiais.

Thirty years later, upon learning that his grave remained unmarked, friends organized a non-profit association, the Les Amis de Beauford Delaney, and successfully raised enough money to install an inscribed granite cap that covers his crypt.

Delaney has been praised since his passing as an important but neglected painter. With a few notable exceptions, the neglect continues. A retrospective of his work at the Studio Museum in Harlem, a year before his death, did little to revive interest in his work. It was not until the 1988 exhibition “Beauford Delaney: From Tennessee to Paris,” curated by the French art dealer Philippe Briet, at the Philippe Briet Gallery, that Delaney’s work was again exhibited in New York, followed by two retrospectives in the gallery: “Beauford Delaney: A Retrospective: 50 Years of Light” in 1991, and “Beauford Delaney: The New York Years, 1929–1953” in 1994.

Delaney’s work has now been exhibited by, among others, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Harvard University Art Museums, Art Institute of Chicago, Knoxville Museum of Art, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Newark Museum, The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, The Studio Museum in Harlem, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and at Columbia University’s campus in Paris. His work has also been exhibited by a number of galleries, including the Anita Shapolsky Gallery, and the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City.

We remember Beauford Delaney in deep appreciation for his significant contributions as a Black and gay artist, and for his contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and to the enduring legacy of our community.