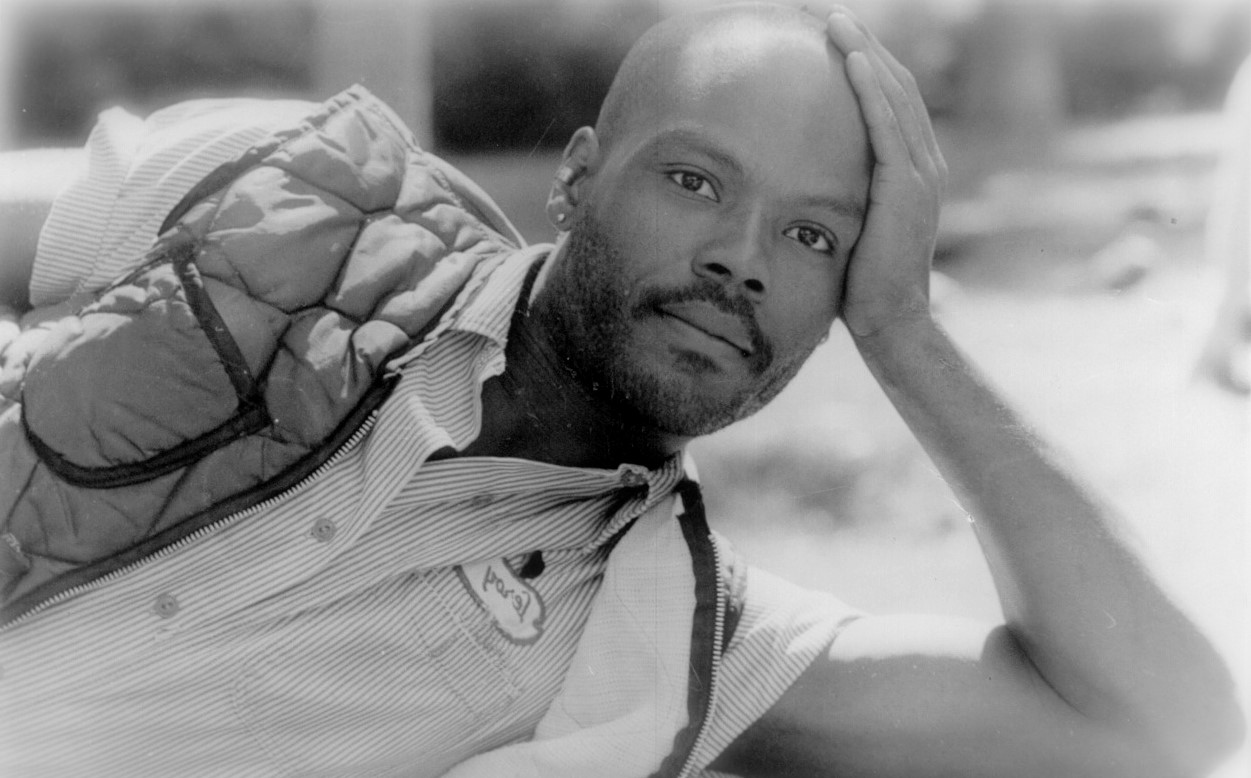

Joseph Beam

Joseph Beam was born on December 30, 1954 (to December 27, 1988). He was an important and visionary writer and thinker, and a gay rights activist who worked to foster greater acceptance of gay men and women in the Black community, by correlating the gay experience with the movement for civil rights in the United States. His groundbreaking anthology, “In The Life,” provided Black, gay men with crucial affirmations of their identities, their aspirations, and their desires.

Joseph Fairchild Beam was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and grew up in West Philadelphia. His father, Sun F. Beam, worked as a bank security guard, and his mother, Dorothy, attended evening classes to obtain her high school diploma. She later earned her Master’s Degree from Temple University, and served for more than twenty years as a teacher and guidance counselor in the Philadelphia school system.

Baptized Catholic, Beam was mostly educated in parochial schools, including St. Joseph School for Boys in Clayton, Delaware, and Malvern Preparatory School, before graduating in 1972 from the old St. Thomas More High School in West Philadelphia. Joseph Beam’s boyhood was difficult and solitary as an only child, although he grew up with a foster brother and sister. Recognized as bright and creative, his parents were encouraged to send him to “high academic” schools. Beam was often the only non-white pupil in his classes.

Beam attended Franklin College in the Indianapolis suburb of Franklin, Indiana, where he was influenced by the civil rights and the Black Power movements, and played an active role in the local Black Student Union. Later, as a member of the Franklin Independent Men, he helped to organize several conferences on campus, and was active in college journalism and radio programming. After graduation in 1976, Beam remained in the Midwest, enrolling first in a Master’s Degree program in communications, and then working as a waiter in Ames, Iowa. He returned to Philadelphia in 1979.

Six feet tall, sturdy, and mustachioed, with penetrating eyes and a distinct assuredness, Joseph Beam had been a visible and very sharp leader in Philadelphia’s Black gay community since the early 1980s. He had long been proud of being Black, and in his mid- to late 20s, he also made it clear that he was proud to be gay.

Beam took a job working at Giovanni’s Room, a cherished bookstore and one of the main contact points for lesbians and gays in 1970s and 1980s Philadelphia. He also worked occasionally as a waiter at several restaurants, including Bread & Co. and Saladalley. Beam became well acquainted with local and national gay figures and institutions. His articles and short stories began appearing in numerous queer newspapers and magazines, including “Au Courant,” “Blackheart,” “Changing Men,” “Gay Community News,” “Philadelphia Gay News,” “The Advocate,” “New York Native,” “Body Politic,” the “Windy City Times,” as well as the “Painted Bride Quarterly.”

The Lesbian and Gay Press Association awarded Beam a certificate for outstanding achievement by a minority journalist in 1984. The following year, he was hired as a consultant by the Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Friends Service Committee (the Quakers). He joined the Executive Committee of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays in 1985, and became the founding editor of their new journal, “Black/Out.” Beam was a member of the Black Writers Guild, and won several awards for his efforts.

Among his most memorable pieces at the “Philadelphia Gay News,” according to managing editor Tommi Avicolli, was an extensive interview with civil rights activist Bayard Rustin. “Joe did excellent work—well-written, well-crafted, and well-thought out,” Avicolli said. “…He was a very articulate voice speaking about the experience of being Black and gay. A lot of people were moved by him.”

Beam began acquiring materials for an anthology of writings by and about Black, gay men in 1982. His goal was to counteract the absence of positive images of gay men of color in the media, and their exclusion from the cultural world of white gay rights activists. Inspired by the humanism of Black feminist and lesbian movements, Beam saw his work as part of a broad effort to correct and redefine the reality of race, sex, class, and gender in the United States. In his writings, he sought to alleviate the alienation of Black homosexuals, and help them to create a community of their own. In 1984, he placed an advertisement in the “Philadelphia Gay News” calling for Black gay writers with the words, “Visibility is survival.” Beam poured himself into editing their manuscripts.

Though ultimately a leading advocate for causes important to the Black gay community, Joseph Beam was not without personal struggles over some issues. He grew angry at injustice. He seemed at times tormented by society’s slowness in accepting—even recognizing—gay African Americans, those close to him said. It was that frustration that triggered his landmark book.

In 1986, Joseph Beam released his completed anthology, “In the Life” (Allyson Press), an astounding collection of essays, poems, interviews, and short stories by 29 Black authors, including several recognized writers, but primarily those who were generally unknown. It was an unprecedented work by Black gay writers marketed to, and for, the Black, gay consumer. The book has been widely described as the first of its kind. In the introduction, Joseph Beam wrote, “The bottom line is this: We are black men who are proudly gay. What we offer is our lives, our loves, our visions…We are coming home with our heads held up high.”

Readers, especially Black, gay men, devoured his book as if it were the first bit of nourishment their hungry souls had ever encountered. For those readers, this was a pioneering work that set an entire universe into motion. It thrilled them, it challenged them, it comforted them, and it inspired them as nothing in print had before. But it was not just rapturously accepted by Black gay men and women. Everyone who read it was touched by this volume of prose and poetry. Some said it was angry, some described it as beautiful, many perceived the abiding love that was contained within its lines of text. But it may be safe to say that everyone, young and old, Black and white, straight and gay, was touched in some way by this monumental work.

“He has to be remembered for helping to lead us out of our silence—and by us, I mean Black gay men, who heretofore had not been speaking out through literature,” said poet and close friend Essex Hemphill. “He has greatly enriched the community at large.”

“For the first time in that book, Black gay men got to tell about their lives and experiences in their own words. Joe was a pioneer,” said James Roberts, a contributor who also worked with him on other projects.

“His book was a major contribution not only to the Black gay community but to the Black community at large, which has often denied the existence of gays within it,” said the Rev. Darlene Garner, a founding board member of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays.

“He was a national figure in the gay and lesbian world,” said Ed Hermance, a friend and owner of Giovanni’s Room.

In the book, Beam described his role: “Not only was I an editor, but often was a confidant and friend to the brothers who submitted their work. I listened to their stories of failed loves, tales of looking for employment…Time after time, their letters and phone calls catapulted me past moments of lethargy and depression. We supported each other.”

It was on a personal level that many remember Joseph Beam, describing him as a man who combined thoughtfulness with a lively spirit. “What stands out was his openness and willingness to be present with people and give whatever he could, even at personal sacrifice,” said Rev. Garner. Mr. Beam, who considered himself spiritual but not religious, used to attend her services at Metropolitan Community Church in Center City as a gesture of support, Rev. Garner said.

After the book’s publication—as he gave lectures and appeared at bookstores across the country— Beam developed a national reputation as a brilliant and sensitive voice for the Black gay community. He begun work on a second anthology, tentatively titled “Brother to Brother,” the title of an essay he wrote in the first anthology. He considered that essay one of his best works.

Beam was working on the book at his Center City home at the time of his death from HIV-related complications (the “Philadelphia Inquirer” reported he died of respiratory and stomach ailments) three days before his 34th birthday in 1989. The project was completed by his mother, Dorothy Beam, and Essex Hemphill, and published under the title “Brother to Brother” in 1991.

“As a writer, Joe was more profound than prolific,” wrote Beam’s friend Craig Harris after his death. “His articles and essays were poetic, containing turned phrases and puns, metaphors in meters that made his writing musical with penetrating meaning. He took great pride in his skill and devoted time to multiple rewrites, crafting his work to create the style which other writers have dubbed ‘Beamesque.’” You can purchase copies of “In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology” and “Brother to Brother: New Writings by Black Gay Men” at http://www.redbonepress.com/

In March 2007, Dorothy Beam was interviewed by Lee Carson, of the Black Gay Men’s Leadership Council. She told Carson, “When Essex (Hemphill) came over to finish the book, he stayed at my house and got himself a job and an apartment…Essex wanted to finish the book because he loved Joe…one of the things Joe wanted was for gay people to be gay people. Joe’s books speak for themselves. When he wrote his books, there weren’t that many Black gay books out. He would have written more but God called him to glory. But I thank Essex for coming over to finish it.”

The contributions of Joseph Beam’s vision and his pioneering anthology, “In the Life,” more than thirty years after it was first published are impossible to calculate. He has inspired and empowered generations of Black, gay men to claim their rightful place in our society. Joseph Beam will be remembered as a man who, though frequently marginalized, possessed a spirit that knew no restrictions, and shared that spirit with the world, at a time when we needed it most. In his honor, the Joseph F. Beam Memorial Scholarship Fund was established for creative writing students at Temple University.

In 2014, Emory University Professor Charles Stephens and Archivist and Curator Steven G Fullwood released their widely anticipated anthology, “Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call.” The book features critical essays, poetry, personal narratives, interviews, and other writings from diverse contributors, calling forth the legacy of Joseph Beam in addition to other leading figures of the 1980s Black gay arts movement. The anthology has received praise from both critics and readers, and many hope that a new generation of readers will be introduced to Joseph Beam and his valuable work.

Ubuntu Biography Project honoree Yolo Akili Robinson founded the Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective, whose acronym, BEAM, honors the late activist. The organization is a collective of advocates, yoga teachers, artists, therapists, lawyers, religious leaders, teachers, psychologists, and activists committed to the emotional/mental health and healing of Black communities.

We remember Joseph F. Beam, and thank him in humble gratitude for his affirming and inspiring writings, for his resilient struggle to make a difference in the lives of others, and for his many contributions to our community.