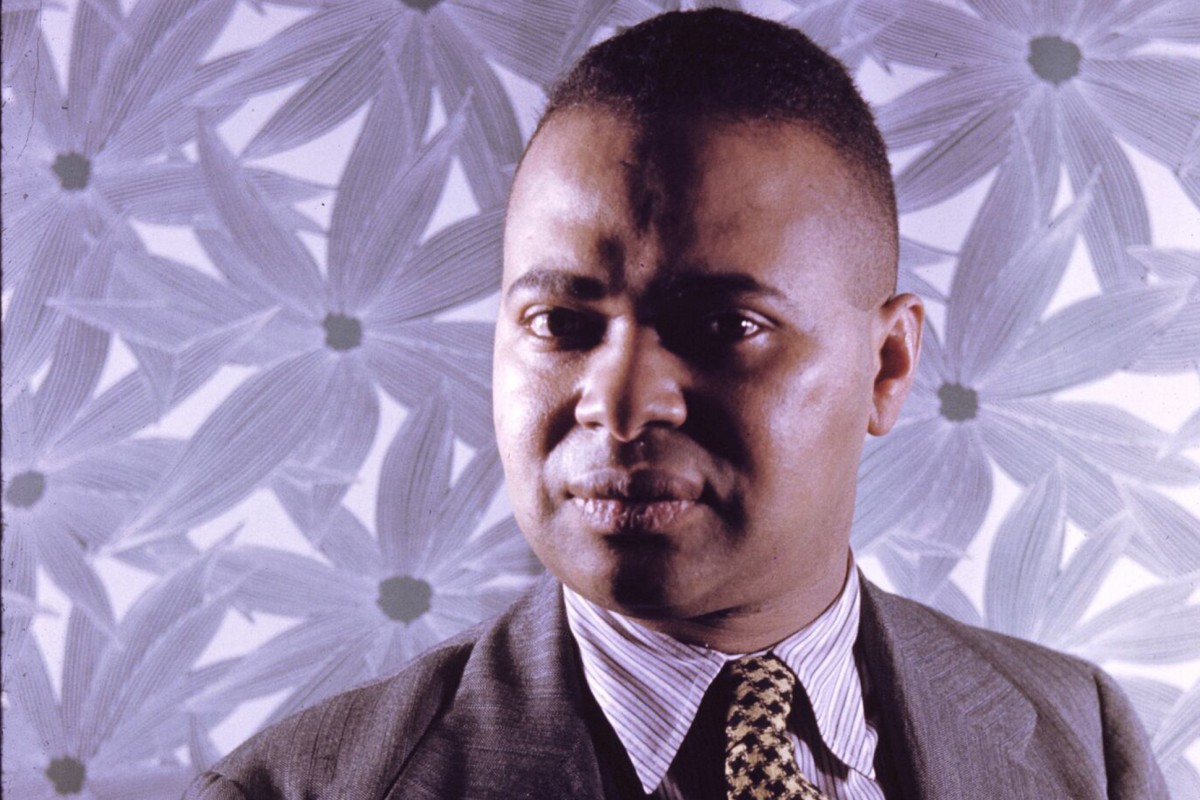

Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen was born on March 30, 1903 (to January 9, 1946). He was an important poet, columnist, editor, novelist, playwright, children’s writer, and educator who was also a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

Given the name Countee LeRoy Porter at birth (in Lexington, Kentucky; New York City; or Baltimore, Maryland, depending on the source), he was the son of Elizabeth Thomas Lucas. The conflicting accounts of his early life can be attributed to the lack of verifiable records, and to different versions of his upbringing that Cullen gave at varying times and circumstances. He was possibly abandoned by his mother, and reared by a woman named Mrs. Porter, who was probably his paternal grandmother. Porter brought young Countee to Harlem when he was nine, and enrolled him at P.S. 27 in the Bronx; she died in 1918.

Very little reliable information exists of his childhood until 1918, when he was taken in, or adopted, at the age of fifteen, by Reverend Frederick A. Cullen and Carolyn Belle (Mitchell) Cullen of Harlem. The reverend was an important local minister, and founder of the popular Salem African Methodist Episcopal Church. It has been suggested that Frederick Cullen was a fire-breathing Christian who carried himself as a rather effeminate man, and who also carried a lot of influence on young Countee.

While in the Cullen home, Countee entered a center of Black politics and culture, and acquired both the name and awareness of the influential clergyman who was later elected president of the Harlem chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Countee Cullen was very discrete about his early life. His adoption was never made official or legally consummated. Indeed, it is difficult to know if Cullen was ever legally abandoned at any stage in his childhood. His biological mother did not contact him until he became famous in the 1920s.

Cullen entered the prestigious, and largely white, DeWitt Clinton High School in Manhattan, where he excelled academically while emphasizing his skills at poetry and in oratorical contests. At DeWitt, Cullen was elected into the honor society, served as editor of the weekly newspaper and their literary magazine, “Magpie,” and was elected vice president of his graduating class. Cullen won a citywide poetry contest as a schoolboy, and saw his winning stanzas widely reprinted. In January of 1922, Cullen graduated with honors in Latin, Greek, mathematics, and French.

After graduating high school, Cullen entered New York University. In 1923, he won second prize in the Witter Bynner undergraduate poetry contest—which was sponsored by the Poetry Society of America—with a poem entitled “The Ballad of the Brown Girl.” At about this time, some of his poetry was appearing in “Harper’s,” “Crisis,” “Opportunity,” “The Bookman,” and “Poetry” periodicals. In 1924, Cullen again placed second in the Bynner contest, and finally won it in 1925. Cullen competed in a poetry contest sponsored by Opportunity, and came in second with “To One Who Say Me Nay”—losing to Langston Hughes’ “The Weary Blues.” Sometime thereafter, Cullen graduated from NYU as one of eleven students selected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

While Cullen’s informal education was shaped by his exposure to Black ideas and yearnings, his formal education was derived from mostly white influences, the only ones accessible to his eager mind at that time. This dichotomy heavily influenced his creative work and his criticism. Cullen loathed white supremacy and racism, but did extremely well at the white-dominated institutions he attended, and won the approbation of white academia.

Cullen was influenced by the works of John Keats, who was reportedly his favorite poet, as well as Percy Bysshe Shelley and A.E. Housman. He would later garner some criticism from his contemporaries of the Harlem Renaissance for his reliance upon traditional European writing structures and verse, though he also incorporated ideas around African American racial origin and experience in much of his work.

Cullen entered Harvard in 1925 to pursue his Master of Arts degree in English, about the same time his first collection of poems, “Color,” was published. Written in a careful, traditional style, the work celebrated Black beauty, and deplored the effects of racism. The book included “Heritage” and “Incident,” arguably his most famous poems. Another poem, “Yet Do I Marvel,” addresses racial identity and injustice, and his “Color” was considered a landmark of the Harlem Renaissance. He graduated from Harvard with his master’s degree in 1926.

The 1920s artistic movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Countee Cullen would flourish during this period, and his writings and ideas would help to build this Renaissance, even as Harlem itself helped to build him. A celebrated young man about Harlem, by 1929 Cullen had in print several books of his own poems, and a collection of poetry he edited, “Caroling Dusk,” with contributions by other Black writers of this era. He worked as assistant editor for “Opportunity” magazine, where his column, “The Dark Tower.” heightened his literary reputation.

In 1928, Cullen was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship to write poetry in France, and before departing, he married Nina Yolande DuBois, the daughter of W. E. B. DuBois, a man who for decades was the acknowledged leader of the African American intellectual community. Few social events in Harlem rivaled the magnitude of this celebrated event, and much of Harlem joined in the festivities that marked the joining of the Cullen and DuBois lineages, two of its most notable families.

The marriage did not fare well. Cullen left his wife to work in France, accompanied by Harold Jackman, a man once described as “the handsomest man in Harlem.” The young, dashing Jackman was a school teacher and, thanks to his noted beauty, a prominent figure among Harlem’s gay elite. Nina Yolande DuBois was furious, and citing his homosexuality, divorced Cullen in 1930, claiming her husband’s relationship with Jackman as a significant factor.

Because of Cullen’s success in both Black and white cultures, he formulated an aesthetic that embraced both cultures. He came to believe that art transcended race, and that it could be used as a vehicle to minimize the distance between the Black and white peoples. In poems such as “Heritage” and “Atlantic City Waiter,” Cullen reflects the urge to reclaim African arts—a phenomenon called Negritude, a literary and ideological movement developed by French-speaking Black intellectuals, writers, and politicians in France. The cornerstone of his aesthetic, however, was the call for Black American poets to work conservatively, as he did, within English conventions. Even the subtitle of his collection, “An Anthology of Verse by Negro Poets,” reflects his belief in the essential oneness of art; it implies no distinction between white poetry and Black poetry, and it assumes there is only poetry, which in the case of “Caroling Dusk,” is simply composed by African American writers.

While Cullen argued that racial poetry was a detriment to the color blindness he craved, he was at the same time so affronted by the racial injustice in America, that his own best verse—indeed most of his work—gave voice to racial protest. The title of Cullen’s 1925 collection, “Color,” was not chosen unintentionally, nor did Cullen include sections with that same title in later volumes by accident.

Cullen’s poetry collections, “The Ballad of the Brown Girl” (1927) and “Copper Sun” (1927), explored similar themes as “Color,” but they were not so well received. His other works of this period include “The Medea and Some Poems” (1935). Cullen’s novel, “One Way to Heaven (1932), depicts life in Harlem. The title poem of “The Black Christ and Other Poems” (1929) was criticized for the use of Christian religious imagery; Cullen compared the lynching of a Black youth for a crime he did not commit to the crucifixion of Jesus. After publication of “The Black Christ and Other Poems,” Cullen’s reputation as a poet waned. From 1934 until the end of his life, he taught in New York City public schools.

When Cullen turned to teaching in 1934, he was determined to find some way other than literature to contribute to social change, but he did not abandon writing entirely. In 1935, he published his version of “Medea,” and collaborated with Harry Hamilton on “Heaven’s My Home,” a dramatic adaptation of his novel “One Way to Heaven.” The play, which was never published, is actually more contrived than Cullen’s novel, but unlike the original work, “Heaven’s My Home” manages to integrate the two plots by introducing a sexual relationship between the protagonists Lucas and Brandon.

Toward the end of his life, in the 1940s, Cullen was relatively successful as a dramatist. He worked on several projects, including “The Third Fourth of July,” a one-act play printed in Theatre Arts in August, 1946. During this period, Cullen rejected a professorship at Fisk University, and instead remained in New York to work with Arna Bontemps on a dramatic version of his novel “God Sends Sunday.” Cullen, who suggested the adaptation, made this endeavor the center of his life, but the enterprise caused him much grief. By 1945, the play had become the musical “St. Louis Woman,” and celebrated performer Lena Horne was expected to star in its Broadway and Hollywood productions. Then disaster struck. Walter White of the NAACP argued that the play, set in the Black ghetto of St. Louis and featuring lower-class and seedy characters, was demeaning to blacks. Cullen was blamed for revealing the seamy side of Black life, the very thing he had warned other Black writers not to do. Many of Cullen’s friends refused to defend him, and some even joined the attack.

But as Cullen argued, the play really deals with human virtues—honor, love, decency, and loyalty. The controversy surrounding it wore on until 1946. In March of that year, “St. Louis Woman” finally premiered on Broadway, featuring songs by Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen such as “Come Rain, Come Shine,” and making singer Pearl Bailey a star. Unfortunately, Cullen had died almost three months earlier, and was to be remembered primarily for the poems he had written in his twenties when he was one of Harlem’s brightest luminaries.

Countee Cullen’s death on January 9, 1946 was unexpected, and caused by uremic poisoning and complications from high blood pressure. For several years after his passing, Cullen was honored as the most celebrated African American in the nation, and by many accounts, is still considered one of the major voices of the Harlem Renaissance. But Cullen’s stature has dimmed in the ensuing decades, as historians and biographers began to focus their attention on other “more courageous” and prolific figures of the Renaissance.

“On These I Stand,” a collection of poems that Cullen had selected as his best, was published posthumously in 1947. The 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library was named for Cullen in 1951, and a public school in New York City and one in Chicago also carried his name. In 2013, he was inducted into the New York Writers Hall of Fame.

We remember Countee Cullen in appreciation for his many contributions to the writings of the Harlem Renaissance, and his advocacy for our community.