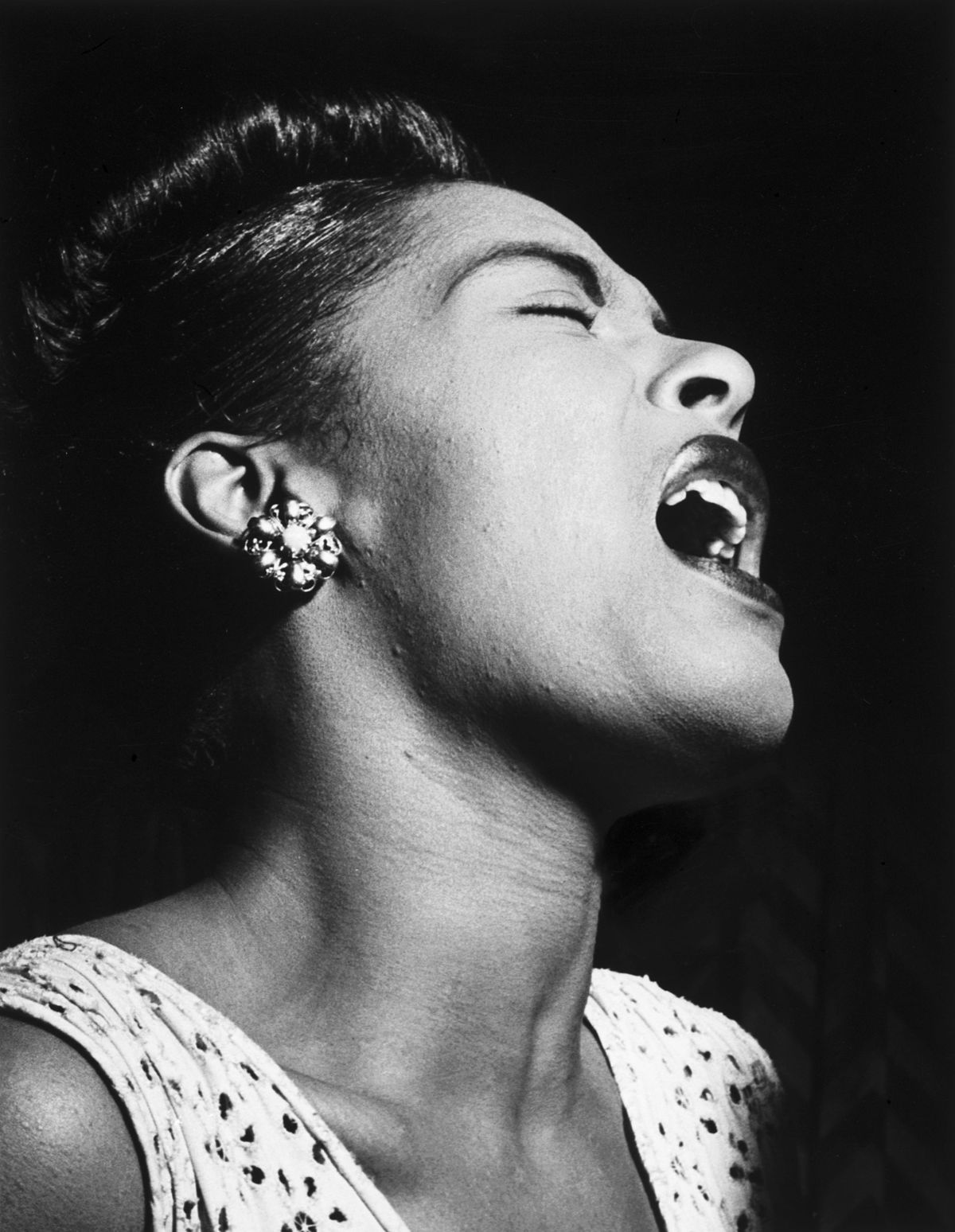

Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday was born on April 7, 1915 (to July 17, 1959). She was an iconic jazz singer, song stylist, and songwriter.

Billie Holiday was named Eleanora Fagan when she was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Sarah Julia “Sadie” Fagan. Her father, Clarence Holiday, a musician, did not marry or live with her mother, who had moved to Philadelphia at the age of thirteen, after being put out of her parents’ home in Baltimore for becoming pregnant. With no support from her own parents, Holiday’s mother arranged for the young Holiday to stay with her older married half-sister, Eva Miller, who lived in Baltimore

Billie Holiday had a difficult childhood. Her mother often took what were then known as “transportation jobs,” serving on the passenger railroads. Holiday was left to be raised largely by Eva Miller’s mother-in-law, Martha Miller, and suffered from her mother’s absences, and being left in the care of others for much of the first ten years of her life.

Holiday frequently skipped school, and her truancy resulted in her being brought before the juvenile court in 1925 when she was not yet ten years old. She was sent to the House of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic reform school, where she was baptized. After nine months, Holiday was “paroled” to her mother, who had opened a restaurant called the East Side Grill; Holiday and her mother worked long hours there. By the time she was 11, Holiday had dropped out of school.

Holiday’s mother returned to their home in December of 1926, to discover a neighbor, Wilbur Rich, raping Holiday. Officials once again placed her at the House of the Good Shepherd in protective custody as a state witness in the rape case. She was released in February of 1927, and found a job running errands in a brothel. During this time, Holiday first heard the records of Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith. By the end of 1928, Holiday’s mother decided to try her luck in Harlem, New York, and left Holiday again in the care of Martha Miller.

By early 1929, Holiday joined her mother in Harlem, and the two ran a brothel at 151 West 140th Street. Holiday’s mother became a prostitute and, within a matter of days of arriving in New York, Holiday, who had not yet turned fourteen, also became a prostitute, turning tricks for five dollars. On May 2, 1929, the house was raided, and Holiday and her mother were sent to prison. After spending some time in a workhouse, her mother was released in July, followed by Holiday in October, at the age of 14.

In Harlem, Holiday started singing in various night clubs. She took her professional pseudonym from Billie Dove, an actress she admired, and the musician Clarence Holiday, her probable father. Benny Goodman recalled hearing Holiday in 1931 at The Bright Spot. As her reputation grew, Holiday played at many clubs, including Mexico’s and The Alhambra Bar and Grill. It was also during this period that she connected with her father, who was playing with Fletcher Henderson’s band.

Holiday was signed to Brunswick Records by John Hammond to record current pop tunes with Teddy Wilson in the new “swing” style for the growing jukebox trade. They were given free rein to improvise the material. Holiday’s improvisation of the melody line to fit the emotion was revolutionary. Their first collaborations included “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” and “Miss Brown to You.”

Holiday began recording under her own name a year later, producing a series of extraordinary performances with groups comprising the swing era’s finest musicians. With their arrangements, Wilson and Holiday took pedestrian pop tunes, such as “Twenty-Four Hours a Day” or “Yankee Doodle Never Went To Town,” and turned them into jazz classics. Most of Holiday’s recordings with Wilson or under her own name during the 1930s and early 1940s are regarded as important parts of the jazz vocal library. She was then in her early to late 20s.

By February of that year, Holiday was no longer singing for Basie, and went to work for Artie Shaw. This association placed her among the first Black women to work with a white orchestra, an unusual arrangement for the times. When touring the American South, Holiday would sometimes be heckled by members of the audience. In Louisville, Kentucky, a man called her a “nigger wench,” and requested she sing another song. Holiday lost her temper, and needed to be escorted off the stage.

In November 1938, Billie Holiday was asked to use the service elevator at the Lincoln Hotel, instead of the passage elevator, because white patrons of the hotels complained. This may have been the last straw for her. She left the band shortly after. There are no surviving live recordings of Holiday with Artie Shaw’s band.

Holiday was recording for Columbia in the late 1930s when she was introduced to “Strange Fruit,” a song based on a poem about lynching written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx. It was eventually heard by Barney Josephson, proprietor of Café Society, an integrated nightclub in Greenwich Village, who introduced it to Holiday. She performed it at the club in 1939. Milt Gabler agreed to record it for his Commodore Records in April of 1939, and “Strange Fruit” remained in her repertoire for twenty years. Holiday’s popularity increased after recording “Strange Fruit,” receiving a mention in “Time” magazine.

Holiday’s mother, Sadie Fagan, opened her own restaurant called Mom Holiday’s. Fagan used money from her daughter when the restaurant was not profitable, and eventually was borrowing large amounts from Holiday. Holiday obliged, but soon fell upon hard times herself. When she asked her mother for some money, her mother turned her down, and an argument ensued. Holiday, in a rage, hollered “God bless the child that’s got his own,” and stormed out of the restaurant.

With help from Arthur Herzog, Jr., a pianist, the two wrote a song based on the line “God Bless the Child,” and added music. “God Bless the Child” became Holiday’s most popular and covered record. It reached number 25 on the record charts in 1941, and ranked third in Billboard’s top songs of the year, selling over a million records. In 1976, the song was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame. In 1946, Holiday recorded “Good Morning Heartache.” Although the song failed to chart, it remained a staple in her live shows, with three known live recordings of the song.

In September 1946, Holiday began work on what would be her only major film, “New Orleans.” Holiday was not pleased that her role was reduced to that of a maid. She recorded the track “The Blues Are Brewin’” for the film’s soundtrack, but little of her acting remained in the film. Holiday’s drug addictions were a growing problem on the set. She earned more than a thousand dollars a week from her club ventures at the time, but spent most of it on heroin. Her lover, Joe Guy, traveled to Hollywood while Holiday was filming, and supplied her with drugs. When discovered, he was banned from the set.

By 1947, Holiday was at her commercial peak, having made a quarter of a million dollars in the three years prior. Holiday placed second in the “DownBeat” poll for 1946 and 1947, and ranked number five on Billboard’s July 1947 issue of “girl singers.” In 1946, Holiday won the “Metronome Magazine” popularity poll.

On May 16, 1947, Holiday was arrested for the possession of narcotics in her New York apartment. During the trial, Holiday received notice that her lawyer was not interested in coming down to the proceedings and representing her. Dehydrated and unable to hold down any food, she pled guilty and asked to be sent to the hospital. At the end of the trial, Holiday was sentenced to Alderson Federal Prison Camp in West Virginia, more popularly known as Camp Cupcake.

After her release in March of 1948, Holiday’s manager decided to throw a comeback concert at Carnegie Hall. Holiday hesitated, unsure whether audiences were ready to accept her after the arrest. She relented and played Carnegie to a sold-out crowd. Holiday did 32 songs at the Carnegie concert by her count. She followed that with a brief, but successful stint in a Broadway show. Holiday was arrested again inside her room at San Francisco’s Hotel Mark Twain on January 22, 1949, over a contract dispute.

Holiday stated that she began using hard drugs in the early 1940s. She married trombonist Jimmy Monroe on August 25, 1941. While still married to Monroe, she became romantically involved with trumpeter Joe Guy, who was also her drug dealer, and she eventually became his common-law wife. She finally divorced Monroe in 1947, and also split with Guy. Billie Holiday’s zest for life included her romances with both men and women, and she frequently has affairs with other celebrities, including actor and director Orson Welles, and actress Tallulah Bankhead.

Because of her 1947 conviction, Holiday’s New York City Cabaret Card was revoked, which kept her from working anywhere that sold alcohol for the remaining twelve years of her life. The Cabaret system ran from 1940 to 1967, and was designed to prevent people of “bad character” from working on licensed premises. Club owners knew blacklisted performers had limited work options, so they would offer them a smaller salary. This greatly reduced Holiday’s earning power. She hadn’t been receiving proper royalties for her work until she signed with Decca, so her main source of revenue was her club concerts. The problem worsened when Holiday’s records went out of print in the 1950s. She seldom received any money from royalties in her later years.

Holiday’s autobiography, “Lady Sings the Blues,” was ghostwritten by William Dufty and published in 1956. Dufty, a “New York Post” writer and editor, was then married to Holiday’s close friend, Maely Dufty. To accompany her autobiography, Holiday released an LP in June 1956 entitled “Lady Sings the Blues.”

On November 10, 1956, Holiday performed two concerts before packed audiences at Carnegie Hall, a major accomplishment for any artist, especially a Black artist of the segregated period of American history. Live recordings of the second Carnegie Hall concert were released on a Verve/HMV album in the UK in late 1961 called “The Essential Billie Holiday.” The liner notes on this album were written partly by Gilbert Millstein of “The New York Times,” who, according to these notes, served as narrator in the Carnegie Hall concerts. Interspersed among Holiday’s songs, Millstein read aloud four lengthy passages from Holiday’s autobiography.

Holiday returned to tour Europe, and while there, made one of her last television appearances for Granada’s “Chelsea at Nine” in London. Her final studio recordings were made for MGM in 1959, with lush backing from Ray Ellis and his Orchestra, who had also accompanied her on Columbia’s “Lady in Satin” album the previous year. The MGM sessions were released posthumously on a self-titled album, later re-titled, and re-released as Last Recordings.

In early 1959, Holiday found out that she had cirrhosis of the liver. The doctor told her to stop drinking, which she did for a short time, but soon returned to heavy drinking. On May 31, 1959, Holiday was taken to Metropolitan Hospital in New York suffering from liver and heart disease. As she lay dying, her hospital room was raided by authorities, and she was arrested for drug possession. Police officers were stationed at the door to her room. Holiday remained under police guard at the hospital until just before she died from pulmonary edema and heart failure caused by cirrhosis on July 17, 1959.

In the final years of her life, Holiday had been progressively swindled out of her earnings, and she died with seventy cents in the bank, and $750 (a tabloid fee) on her person. Her funeral mass was held at Church of St. Paul the Apostle in New York City.

A 1972 film starring Diana Ross, and later a Broadway show starring Audra McDonald, were made about Holiday’s life and times.

We remember Billie Holiday, and recall with great joy her many contributions to music and our community.