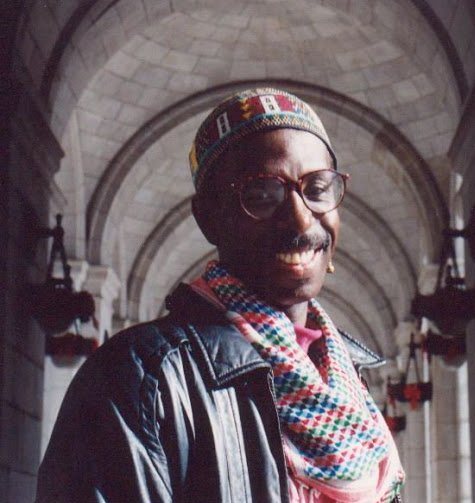

Reggie Williams

Reggie Williams was born on April 29, 1951 (to February 7, 1999). He was a health care professional, a charismatic community leader, a highly effective early activist for HIV prevention and treatment, and a caregiver and community builder who created lasting alliances with other communities and interests to achieve greater acceptance of the SGL/LGBT community of African descent.

Reggie Williams was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the second oldest of nine children of Jean Carpenter Williams, and grew in the Washington Terrace housing projects in the city’s Walnut Hills neighborhood. He attended Columbian Elementary School, Samuel Ach Junior High, and graduated from Cincinnati’s Withrow High School before enrolling at Cincinnati General Hospital (now University of Cincinnati Medical Center), where he received his degree as an x-ray technologist in 1971. Williams was known for his remarkable tenor voice, and was called upon to sing in his church choir as a child and at Withrow High School. In his teens, he joined a gospel group that toured local churches and competitions in the greater Cincinnati region.

Williams never felt as if he were living in the closet, so his “coming out” was never really an issue for him. “I have often been asked when did I ‘come out,’ or when did I know that I was gay? And I always have to laugh, and say that I always felt gay. Even if that was not the term used when I was growing up. But, it is really true for me. I have felt attracted to boys from about age six or seven. And I always liked to do things that were very un-boy like. Trying to cook, bake, and I loved playing with my sister’s dolls. I used to love to comb my mother’s hair,” he recalled.

In 1969, after earning his degree, Williams and his partner, Alphonso Freeman, moved from Cincinnati to Los Angeles, California, where he had no difficulty finding work as a radiology technician. Williams eventually secured a job at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. As with so many others in Los Angeles, he had aspirations to become a model and actor. At Cedars-Sinai, Williams first began seeing patients who were severely ill with a mysterious ailment that would become known as Gay-Related Immune Disease. Years later, Williams would recall visiting The 8709, a popular bathhouse located across the street from Cedars-Sinai, and wondered out loud if that’s where he became infected during “graveyard” shift lunch breaks.

Williams split up with Freeman when he met Tim Isbell in LA. Together, they moved to San Francisco, where Williams accepted a position at University of California – San Francisco. By the mid-1980s, AIDS in San Francisco was approaching epidemic proportions, and Williams was one of the first to recognize that information and prevention efforts were not reaching the gay and bisexual Black community.

Williams called a meeting that resulted in the AIDS Task Force of the San Francisco chapter of Black and White Men Together (now known in some places as Men of All Colors Together), and became its co-chair in 1984. He would go on to serve as founding executive director of the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention, launched in 1987, as a primary HIV prevention project operated primarily through the national network of chapters of Black and White Men Together (BWMT). NTFAP was the recipient of one of the first national community-based grants from the US Centers for Disease Prevention & Control. For more info, see https://sites.google.com/site/reggiewilliamsexhibit/ntfap.

The Task Force developed groundbreaking culturally sensitive research and training programs, and responses to the growing problem that was impacting gay men of African descent. It became the first federally-funded project focusing on African American men who have sex with men. The National Task Force on AIDS Prevention was led by both Williams and his dear friend Phill Wilson, another early hero of the struggle against HIV/AIDS. Wilson currently leads the Black AIDS Institute, which he founded in 1999.

Driven by his mission to make a difference in the lives of others, and the need to call attention to a major crisis, Williams often took his cause to the streets. But he did not present himself as an angry man or try to motivate others with frustration and rants. Friends recounted that he had the most wonderfully disarming smile, and his enthusiasm as he did his righteous work was infectious, making others happy to join in.

But in the late-1980s, as a health crisis raged on, the medical community was in chaos, social services networks were immobilized by fear of offending evangelicals if they showed compassion towards gay men, and government entities in America were in deep denial. It was not a good time to be a gay man, forced to confront homophobia and religious hatred at every turn. And if you were a Black gay man, you had to slay the many dragons of racism, injustice, and homophobia before you could go on the offensive against the core issues of ignorance and misinformation. The very communities that you most needed to connect with, wanted no connection with you.

When you factored in a health crisis that even doctors and other medical professionals were frightened of, sometimes to the point of ignoring their solemn oath, you were confronted with a complex crisis that few wanted to address. When death came, as it so often did, clergy of all faiths embraced their theology, while too often ignoring the humanity of those around them who needed comfort and understanding, but often received only condemnation. Families refused to acknowledge that their sons, brothers, and fathers were homosexual, and obituaries often cited “heart-failure” or “pneumonia” as a cause of death, while gay friends and lovers were often discouraged from attending their funeral services.

It was this very scenario that added to the fear, ignorance, and hysteria of the AIDS epidemic. It was this scenario, in which countless heroes and sheroes stepped up and stepped in, making a profound difference in the midst of the crisis by bridging the gap left by others. Williams was one of those heroes whose leadership made a difference, and whose actions changed the way a nation looked at HIV and AIDS. He helped to sound the alarm and shift the focus (albeit temporarily) to the growing crisis among Black, gay, and bisexual men. “You need to look at a different model from one that works for gay, white men,” Williams contended. “There is a host of other issues we gay men of color deal with on a daily basis. We have to deal with impoverishment, homophobia in our own community, and pervasive racism in society.”

Around this time, Williams began to experience extreme fatigue, and weight loss that drove him to see his doctor. He was shocked to receive the news he had dreaded: a tentative diagnosis of AIDS-related complex (later called HIV). As he told Marilyn Chase of “The Wall Street Journal,” “I was holding out…I took the test to prove my physician wrong. I wanted to wave the paper in his face. That didn’t happen. I shut down emotionally.” His partner of seven years, Tim Isbell, tested negative at the time. Williams and Isbell, a minister’s son and the director of a church choir, spoke openly of their disparate test results, and how they were coping.

Photographer Barbi Schreiber published “One Life for Another: The Survivor’s Story” in 1987, which included a series of photos at the couple’s home on Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Schreiber’s notes stated of Williams: “Behind his handsome portrait is the story of a hero, one of the few who dared to be publicly recognized as a person with AIDS in a time when the HIV infection was still considered a ‘gay plague’ that could get you evicted or fired.” Williams was quoted as telling her, “I have had a wonderful life—I can’t say that enough; if I had to die tomorrow it would be just fine, as I have lived—you have to have lived to be able to accept your own death. I’ve had a lot of love and support from my family, my lovers, my friends. I have been lucky enough to have been surrounded by wonderful people and have tried to circumvent those who have not been.”

In 1989, Williams led a group of five gay men of color to launch the San Francisco Gay Men of Color Consortium, a coalition of Black, Latin, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American gay men of color AIDS organizations in San Francisco. He also served on the boards of the NABWMT, the AIDS Action Council in Washington DC, and numerous other organizations related to African Americans, lesbians and gay men, and AIDS, including the HIV Health Services Planning Council, commonly called the CARE Council, which oversaw the distribution of the federal Ryan White CARE Funds, and of which he was a charter member. Williams formed the Yours in the Struggle Project with Al Cunningham, a close ally from his time at The National Task Force on AIDS Prevention.

Williams’ diagnosis did not slow him down. In December of 1989, he was photographed at a protest demonstration in Washington, DC, demanding more federal funds for AIDS research, as well as food, shelter, and health care for AIDS patients around the nation. In San Francisco, Williams spoke at an annual spring ritual, in which thousands of marchers walked from the Castro district down Market Street to City Hall in the annual AIDS Candlelight Memorial. His struggle against homophobia in the Black community and racism among white gays took on a new sense of urgency. He was quoted as saying, “My personal struggle with AIDS has forced me to demand respect and dignity from my people. Black, gay men need to be able to come home.”

Williams and four other HIV-positive Black gay men were featured in Marlon Riggs’ groundbreaking film “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” (No Regret) in 1992. In July of that year, he attended the VIII International Conference on AIDS, in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. While attending the conference, he met and befriended Wolfgang Schreiber of Amsterdam, who would later become his partner and caregiver. The conference had been moved from Harvard University to Amsterdam because of a 1987 law barring HIV-positive persons from entering the United States; this draconian legislation remained in place until 2009. It was repealed when President Obama signed the Ryan White Act IV, which lifted the HIV Travel and Immigration Ban.

In April of 1993, the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation drew an estimated crowd of nearly one million. Williams was one of the invited speakers and the only person to discuss AIDS in any detail. His address was carried in an article in “Z” Magazine, “United We Stand, Divided We Grovel—Queers and the Health Care Debate.” Later that same day, Schreiber and Williams took part in a “Wedding-Manifestation,” with hundreds of participants demonstrating for equal rights.

Because of his declining health, Williams retired from his position as executive director of the NTFAP in February of 1994. He was honored at a tribute Yours in the Struggle banquet on February 26. By April, Williams moved to Amsterdam, able to legally immigrate to the Netherlands as Schreiber’s life partner. Same-sex partners now had the same immigration rights as everybody else, and Williams was able to obtain a residence permit in the Netherlands, and health insurance through Schreiber’s health plan.

Williams wrote his first “Letter from Amsterdam,” which was published in the new gay magazine “Wilde” in 1994, and vowed to continue the series. In the spring of 1995, he survived pneumocystis pneumonia, and wrote “The Second Letter,” which was never published. Williams became involved in AIDS prevention work in Amsterdam, joining forces with a gays and lesbians of color group, Strange Fruit The Real, where he helped to organize safer sex and culture workshops from 1995 on.

Marlon Riggs died in April of 1994, and Williams’ dear friend Essex Hemphill passed on November 4, 1995. At a remembrance service for Hemphill in Amsterdam, Williams said, “I am not here tonight to mourn Essex, but to celebrate his life. To celebrate the richness he gave us all, especially Black gay men…Essex’s works inspired, motivated, and helped us look inside ourselves to be able to empower ourselves to rise above homophobia, racism, sexism, and classism. To stand tall and proud as Black Gay men.”

Day-to-day life was becoming more difficult for Williams, but he remained as strong and determined as ever. But by July of 1996, he was diagnosed with colon cancer; many hospital stays and many new procedures would follow. A year later, new hope was on the horizon with the release of new AIDS pharmaceuticals. Williams became one of the first patients in the Netherlands to receive the new treatments. By 1997, his health began to stabilize, and Williams and Schreiber traveled to France, Germany, Britain, Canada, and the United States. Williams attended the Gay and Lesbian Leadership Conference, in Long Beach, California in 1997, and while at home in Europe, he continued to take part at conferences in the US, when his health allowed, and critically watched the developments at the NTFAP until it’s closing in June of 1998.

Reggie Williams Day was designated by the California State Senate on September 11, 1996, in honor of Williams’ “dedicated service as President of the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention.” His health continued to decline and rebound, but he was still able to carry on the struggle through the good days. The photobook, “At Home in Amsterdam—Portraits of Gay Men from All over the World” by Lutz van Dijk, features Williams with pictures captured in 1996, and published in 1998. In January of that year, Williams was featured in the photobook “Black Inspiration” by Jürgen Jansen. He was interviewed by John-Manuel Andriote for the book “Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America” in 1999.

Due to his declining health, Williams’ last public appearance was at the Gay Games V in Amsterdam in 1998. The highlight for Williams was seeing his friend, South African freedom fighter and LGBTQ advocate Simon Nkoli. Nkoli would die later that year, on the eve of World AIDS Day 1998.

On October 20, 1998, Williams and Schreiber officially registered their partnership in Amsterdam, and in December, they took what would be Williams’ last trip to California. The San Francisco AIDS Office had started Project Reggie, a computerized client registration and information/referral system named in his honor. You can learn more about Reggie Williams’ life and legacy at www.reggiewilliams.org or www.reggiewilliams.net.

Williams and his beloved partner returned to their home in Amsterdam, and on February 7, 1999, Williams lost his long struggle, and passed peacefully at the Academisch Medisch Centrum Hospital. His funeral service was held at Westerveld Crematorium in Driehuis, Netherlands. Williams’ ashes were buried at his mother’s grave in Cincinnati, Ohio. Memorial services celebrating his life and honoring his contributions were held in Amsterdam, San Francisco, and in Cincinnati.

In the United States, National Black AIDS Awareness Day is observed each year on February 7, which coincides with the anniversary of Reggie Williams’ passing. A room at the San Francisco LGBT Community Center is dedicated in his honor. Williams also is remembered in a photo exhibit sponsored by the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society, featuring photographic portraits of people with AIDS taken by Barbi Schreiber in the late 1980’s.

We remember Reggie Williams in deep appreciation for his visionary leadership, his powerful advocacy for AIDS treatment and prevention, and for his many contributions to our community. Special thanks to Albert Cunningham, Wolfgang Schreiber, and Reggie Williams’ sisters, Connie and Denise, for their assistance and support in creating this biography.