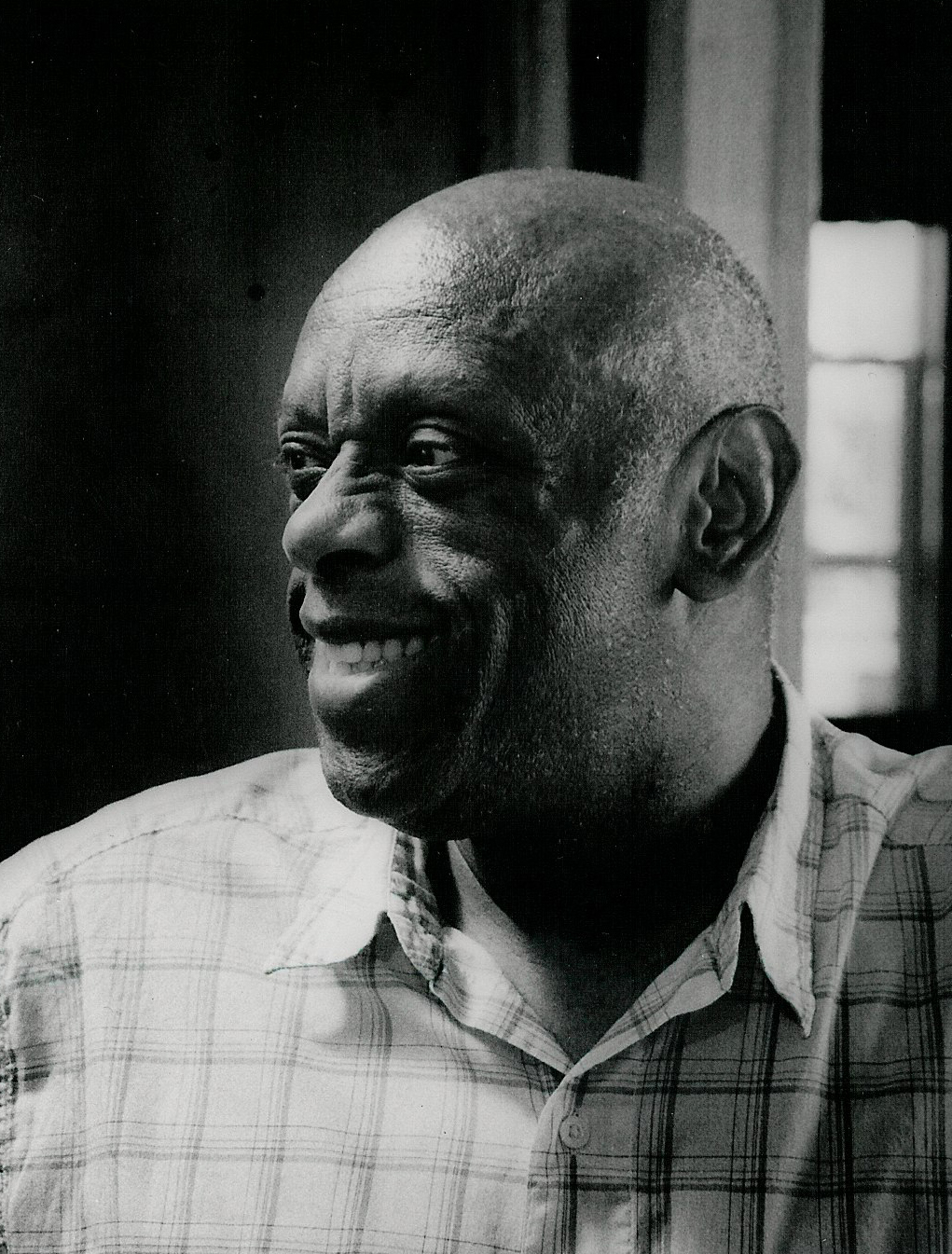

Rupert Kinnard

Rupert Kinnard was born on July 21, 1954. He is a celebrated cartoonist, successful art director, beloved illustrator, popular guest house host, and a respected community builder.

Rupert Earl Kinnard was born in Chicago, Illinois, the only son of Rufus Kinnard, who was a cab driver and groundskeeper, and his mother, Viola Hollins, a homemaker who eventually became a nurse’s aide. He attended Fort Dearborn Elementary School, Morgan Park High School for his freshman and sophomore years, and then enrolled at the Chicago Public High School for Metropolitan Studies. He also attended classes at the Art Institute of Chicago.

After graduating high school in 1973, Rupert took classes at the American Academy of Art, and in 1976, enrolled at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in art three years later. During his senior year at Cornell College, Rupert was chosen as editor of the 1978-1979 “Royal Purple” yearbook, and also served as president of Students for Black People for a semester, and as a popular DJ at the Cornell College radio station, KRNL.

After expressing himself artistically in a number of ways as a child, Rupert discovered superhero comics at around age eleven. At first, he learned to draw all the heroes with whom he became familiar—Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, and then on to Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Daredevil and Thor. Eventually, he started creating his own characters, and soon, with his growing idolization of boxing champion Muhammad Ali, he became dismayed when he realized that all the superhero comics that he was collecting only featured white characters to admire. Even worse, the superheroes that he had created were also white, and they, in no way, reflected his own community.

Rupert immediately started creating Black superheroes, and became enamored of one of his creations in particular, a revolutionary he named Superbad. The creation was highly influenced by Rupert’s love of Ali and a growing respect for Malcolm X as a Black leader. Rupert continued to draw and re-draw his own characters, perfecting his craft as he pursued ways to support himself through his own creative drive.

In 1974, while working in the Promotion Department at the “Chicago Sun-Times,” Rupert convinced the art director to give him a chance to illustrate an article. His assignment was to depict Redd Foxx as a nightclub entertainer and a TV personality. After the illustration was accepted and published on the cover of the Arts & Entertainment section of the paper, he was elated. Having his work published and seen by thousands of people lifted his spirits up to new heights. It also gave Rupert his first glimpse into how satisfying it might be to be an art director.

Two years later, during summer break from Cornell College in 1976, he created the Brown Bomber as a kinder and gentler superhero based on yet another boxer, Joe Louis (who was also famously known as the Brown Bomber). The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. also influenced his work, and he proclaimed his Brown Bomber to be the world’s first Black non-violent superhero. From there, the Brown Bomber became a weekly fixture on the editorial page of the Cornell newspaper, “The Cornellian.”

There was nothing about the Brown Bomber that would have lead people to assume he was a gay character, but that changed in 1979. The Black student group decided to create a fundraiser to establish an African American scholarship fund for new Black students. By that time the Brown Bomber had pretty much become a popular school mascot, so it was decided that 300 Brown Bomber t-shirts would be sold to raise money. In the end, students, professors, and faculty members purchased all 300 t-shirts, and shortly after, Rupert created a series of strips that featured the Brown Bomber coming out of the closet.

Rupert Kinnard created Rupe Group Graphics in 1978, and a year later, moved to Portland, Oregon and ended up having the Brown Bomber published in a couple of the local LGBTQ publications. Three years later, he created Diva Touché Flambé, and she joined the Bomber in a new strip called Cathartic Comics within the pages of Portland’s most significant queer newspaper, “Just Out.” He was with that publication from the very beginning as art director, and within its first year they won the 1983 Gay Press Association Award for outstanding achievement in overall design.

The 1980s were a particularly eye-opening era for Rupert. “For what seems to have been a brief moment in time, I felt we were experiencing what it might have been like to live during the Harlem Renaissance,” Rupert recalls. “I rubbed shoulders with the likes of Nikki Giovanni, Joseph Beam, Brian Freeman, Afro Pomo Homos, Reggie Williams, Barbara Smith, Linda Tillery, Evelyn C. White, Keith Boykin, Kerrigan Black, Alan Miller, Phill Wilson, Blackberri, Marlon Riggs, Essex Hemphill, and others.” He adds, “Many of those people are truly my unsung sheroes/heroes.”

Rupert has experienced a rewarding career as a graphic designer and art director for a number of alternative publications, progressive groups, and organizations. Cathartic Comics became a “sub-underground” syndicated strip that appeared in publications in San Francisco, the Bay Area, Chicago, Alabama, Chicago, and Los Angeles. His characters and other illustrations were featured in the book, “Young, Gay and Proud,” published in 1991. Later that same year, the book “B.B. and the Diva: A Collection of Cathartic Comics” was published by Alyson Publications.

According to Rupert, he has thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to share his political views through his comics. It allows him the opportunity to address some very serious subjects in a medium that encourages a whimsical view, highlighting the humor, irony and absurdity of it all. Rupert enjoys giving people an opportunity to think about certain subjects in ways that might be different, giving them a new, more balanced perspective. He adds, “I love sharing the Brown Bomber and the Diva Touché Flambé side of myself with others. They are, of course, my yin and yang.”

Rupert is passionate about his work as a graphic designer, and is proud of his efforts in support of progressive ideas. He has worked with Oregonians Against the Death Penalty, the National Organization for Women (NOW), National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), Multnomah Human Rights Commission, Portland State University, Portland Town Council, Worker’s Organizing Committee, National Lawyers Guild, the Lesbian Community Project, National Black Justice Coalition, Disability Art, and the Culture Project, helping to raise the quality of their promotional materials as they reach out for community support.

Rupert Kinnard has also been involved with a book project, “The LifeCapsule Project.” It brings together nearly every element of work that he’s completed into a graphic memoir, a time capsule, an oral history, photo album, and scrapbook. He hopes the project will spark individuals to explore unique experiences that helped form them into the people they have become, revealing both their journey and their truth. Rupert also hopes to encourage others to acknowledge the various communities of which they have been a part, and realize we all have shared experiences and benefit from sharing our observations with others.

Rupert was influenced by artist and friend, Alison Bechdel, who creates the nationally syndicated strip, “Dykes to Watch Out For.” He admires her work and loved her graphic biography, “Fun Home.” It inspired him to begin creating his own biography, as a celebration of the communities and the kind of social phenomena that he’s been involved in. Rupert has been particularly affected by the southern migration of African Americans from the south to the north. His family migrated from Mississippi to Chicago, and he feels very much a product of the civil rights movement, alternative education, the lesbian and gay rights movement, the feminist movement, alternative press, and on and on. He is focused on something autobiographical to share with other people to show what it was like being a part of each of these movements.

On growing up Black and gay, Rupert recalls, “The challenges I faced as a young LGBTQ man growing up had to do with dealing with what it meant to be a young Black male in this society and then, hot on the heels of that struggle, dealing with what it meant to be a gay man. Being a young Black man who lived in an all-Black community was comfortable for me because I knew of nothing else. There was such a lack of visibility of Blacks in the media that it was always a big deal to see yourself represented on TV or film. But bit by bit, I found myself being exposed to the fact that racially, the difference made a difference.”

He adds, “I think it is almost a rite-of-passage for most people of color to recall what could be considered their racial ‘end of innocence’ moment. For me, there was actually a pivotal event that signaled a racial awakening. When our family moved to the south side of Chicago and I ended up at a grade school that was in the process of integrating, I encountered being around white kids for the very first time. Slowly but surely, I became aware that I was considered to be a second class citizen.”

The other traumatic memory he had involved getting pushed by white boy. Instinctively, Rupert yelled, “Nigga, stop it!” He was confused when they all laughed at him, saying, “You have a lot of nerve—you’re the nigger.” He had innocently thought that word was interchangeable with the word “chump” or “jerk,” and had never connected it to being a derogatory term intended for him, as a “negro.” He now says that was “literally, a defining moment.”

Rupert explains his experience as a young gay man as a gradual acceptance that he was attracted to other males, the way other boys were attracted to girls. But his attraction was second nature to him and felt natural. He says he never questioned it; it became one more way that he appreciated being different from other boys, and it set him apart. He adds that he rarely felt a need to fit in with the crowd, despite knowing that his father clearly wanted him to be more like his heterosexual peers.

Rupert Kinnard never experienced an actual coming out, never desired the attention of girls, and never dated or strayed from who he knew himself to be. The only struggle he had with being gay was when he attended bible studies in church. He believed everything he was taught…until he was told that to identify as gay was a sin. He says, “That simply didn’t make sense to me. I was a bit concerned about it until I read the book ‘The Church and the Homosexual’ by John J. McNeill. It debunked so much of how people interpreted the bible passages, and that was all I needed. At that time, my belief in God wouldn’t allow me to think of ‘my God’ as a ‘petty God’ who was prone to silly little human failings.”

Today, Rupert enjoys his life Portland with his partner, Scott Stapley. “The one thing that makes me feel like I am the luckiest man in the world is Scott. I would have never imagined that I would ever meet someone who would let me be me.” Rupert and Scott own a rental home, the Kinley Manor Guest House, right next door to their home. They are happy to welcome you when you are seeking accommodations in Portland. Feel free to check it out at www.kinleymanor.com.

Also known as “Professor I. B. Gittendowne, Rupert draws strength and delight from the Black SGL/LGBTQ community, and says that it is uniquely different from other communities. “There is so much to be said about the “FLAVAH” of our culture. I find a home in being with other Black queer folks. I discover more about myself when I am around my people. I see my beauty reflected in the beauty I see when I am in the company of my people. I simply feel that we are to be celebrated for all that is unique about us.”

We thank Rupert Kinnard for his countless contributions to the world of comics, art and illustrations, and for his longtime support of our community.