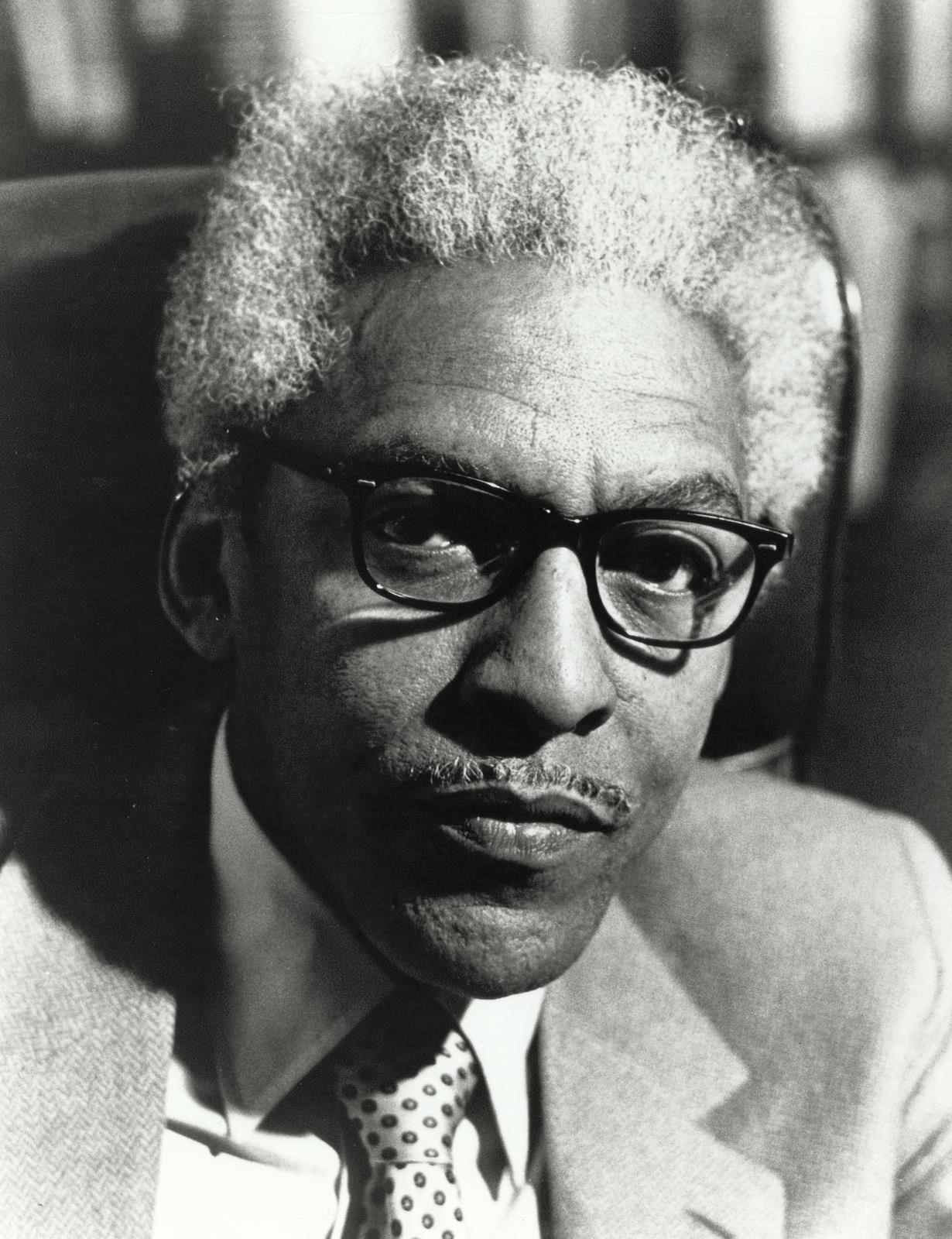

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin was born on March 17, 1912 (to August 24, 1987). He was an important pacifist, event organizer, human rights advocate, and a leading voice in shaping the strategies and objectives of America’s civil rights movement.

Bayard Taylor Rustin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He had no relationship with his father, and his 16-year-old mother, Florence, was so young Rustin thought she was his sister. He was raised by his maternal grandparents, Janifer and Julia Rustin. Julia Rustin was a Quaker, although she attended her husband’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. She was also a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Many NAACP leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson were frequent guests in the Rustin home. From his grandparents, Rustin took his Quaker values, which, in his words, “were based on the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal,” according to author Jervis Anderson in “Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen.” As a young man, Rustin campaigned against Jim Crow laws in West Chester.

As a teenager, Rustin wrote poems, played left tackle on the high school football team, and, according to lore, staged an impromptu sit-in at a restaurant that would serve his white teammates but not him. When Rustin told his grandmother he preferred the company of young men to girls, she simply said, “I suppose that’s what you need to do.”

In 1932, Bayard Rustin entered Wilberforce University in Ohio operated by the AME church, and got involved in a number of campus organizations, including the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity. He left Wilberforce in 1936 before taking his final exams, and moved to Harlem during the time of the Harlem Renaissance. Rustin became active in the campaign to free the nine African Americans that had been falsely convicted for raping two white women on a train. Known as the Scottsboro Case, Rustin was energized by what he believed was an obvious case of white racism.

In 1937, Rustin enrolled at City College in New York City, where he devoted himself to singing, performing with the Josh White Quartet, and in the musical “John Henry” with Paul Robeson. He also joined the Young Communist League. Though Rustin soon quit the party after it ordered him to cease protesting racial segregation in the U.S. armed forces, he was already on the radar of J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

In 1941, Bayard Rustin met the African American trade union leader, A. Philip Randolph. A member of the Socialist Party, Randolph was a strong opponent of communism. Rustin helped Randolph plan a proposed March on Washington in June of 1941, but the protest was called off when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defense industries and federal bureaus, known as the Fair Employment Act.

Disappointed when the 1941 March on Washington was called off, Rustin joined pacifist Rev. A.J. Muste’s Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and when FOR members in Chicago launched the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942, Rustin traveled around the country speaking out. Two years later, he was arrested for failing to appear before his draft board, and refusing alternative service as a conscientious objector. Sentenced to three years, Rustin ended up serving 26 months, angering authorities with his desegregation protests and open homosexuality to the point they transferred him to a higher-security prison.

Once released, Rustin embarked on CORE’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, an early version of the Freedom Rides, to test the Supreme Court’s ruling in Morgan v. Virginia (1946) that any state forcing segregation on buses crossing state lines would be in violation of the Commerce Clause. It was a noble attempt, but Rustin soon found himself on a chain gang in North Carolina.

As part of his deepening commitment to nonviolent protest, Rustin traveled to India in 1948 to attend a world pacifist conference. Mahatma Gandhi had been assassinated earlier that year, but his teachings touched Rustin in profound ways. “We need in every community a group of angelic troublemakers,” he wrote after returning to the States. “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

In January 1953, Rustin, after delivering a speech in Pasadena, California, was arrested on “lewd conduct” and “vagrancy” charges, allegedly for a sexual act involving two men in an automobile. With the FBI’s file on Rustin expanding, FOR demanded his resignation. That left Rustin to conclude, “I know now that for me sex must be sublimated if I am to live with myself and in this world longer,” according to “Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin.”

Bayard Rustin recognized Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership early, and helped to organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to strengthen King’s leadership within the Civil Rights movement. In 1956, on the advice of labor leader and activist A. Philip Randolph, Rustin traveled to Alabama to lend support to Dr. King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. While remaining out of the spotlight, Rustin played a critical role in introducing King to Gandhi’s teachings while writing publicity materials and organizing carpools. When Rustin arrived in Montgomery to assist with the bus boycott, there were guns inside MLK’s house, and armed guards posted at his doors. Rustin persuaded King and the other boycott leaders to commit the movement to complete nonviolence. Rustin later demonstrated against the French government’s nuclear test program in North Africa.

Rustin experienced one of the lowest points in his career in 1960, and the author of this crisis wasn’t J. Edgar Hoover; it was another Black leader, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. of New York. Angry that Rustin and King were planning a march outside the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, Powell blackmailed King under the threat that if he did not drop Rustin, Powell would tell the press King and Rustin were gay lovers. Regardless of the fact that Powell had concocted the charge for his own malicious reasons, King, in one of his weaker moments, called off the march and put distance between himself and Rustin, who reluctantly resigned from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was led by King. For that, King “lost much moral credit…in the eyes of the young,” writer James Baldwin wrote in “Harper’s” magazine. Fortunately for the nation, Rustin put the movement ahead of this vicious personal slight.

The idea for the 1963 march again came from A. Philip Randolph, who wondered if younger activists were giving short shrift to economic issues as they pushed for desegregation in the South. In 1962, he recruited Rustin, and the two began making plans, this time to commemorate the centennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

After Bull Connor turned firehoses and attack dogs on children in Birmingham, the national sentiment shifted. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had not shown much interest in the earlier overtures from Rustin and Randolph, began to talk excitedly about a national mobilization, as if the idea were brand new. Rustin traveled to Alabama to meet with King, and expanded the march’s focus to “Jobs and Freedom.” From the march’s headquarters in New York, Rustin looked forward to leading the planning coalition of the “Big Six” civil rights organizations: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), CORE, SCLC, the National Urban League, the NAACP, and Randolph’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. But Rustin’s past again came into play when Roy Wilkins of the NAACP refused to allow Rustin to be the front man. “This march is of such importance that we must not put a person of his liabilities at the head,” Wilkins reportedly said of Rustin. As a result, Randolph agreed to serve as the march’s director, but insisted that Rustin serve as his deputy.

Their challenges were huge: unite feuding civil rights leaders, fend off opposition from Southern segregationists who opposed civil rights and from Northern liberals who advocated a more cautious approach, and figure out the practical logistics of the demonstration itself. On the last point, Rustin later said, “We planned out precisely the number of toilets that would be needed for a quarter of a million people…how many doctors, how many first aid stations, what people should bring with them to eat in their lunches.”

The entire time, Rustin feared interference from the Washington police and the FBI, but it came from the Senate floor three weeks before kickoff when Strom Thurmond of South Carolina attacked Rustin personally. It didn’t matter that Thurmond was hiding a daughter he had fathered with an African American woman who was his family’s maid, Rustin was a gay ex-communist and, in 1963, reading from his FBI file made political hay.

Bayard Rustin had just eight weeks to plan the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and by all accounts his leadership was visionary and masterful. In addition to negotiating with warring factions, he organized an unprecedented bus convoy, and wrote briefings for participants that explained the what, where, when, and why of the March. Rustin coordinated food, health and sanitation facilities, child care, and overnight accommodations. He identified captains, marshals, and the all-important transportation coordination for the March participants.

The march itself, of course, turned out to be a tremendous success, including those glorious moments when the official estimate of 200,000 was announced (there was as many as 300,000, according to some estimates); when Marian and Mahalia sang; when Mrs. Medgar Evers paid tribute to Negro Women Freedom Fighters; when John Lewis and Dr. King spoke; and when Bayard Rustin read the march’s demands. And perhaps the most poignant statement of the power of nonviolence was that there were only four arrests, Taylor Branch writes in “The King Years”—all of them of white people.

Afterward, the leaders of the “Big Six” met with President Kennedy at the White House. Rustin remained out of sight, though he and Randolph did make it onto the cover of “Life” on September 6. Eight days later, four young girls went to their deaths in the Birmingham church bombing. In November, President Kennedy was gunned down, leaving President Lyndon Johnson to shuttle the Civil Rights Act through Congress. It was signed in 1964, the same year Dr. King received the Nobel Prize, with Rustin planning the logistics of his trip to Oslo. It was, to say the least, history at its most dramatic, shocking—and unpredictable—at every turn.

As memories of the march faded and the movement entered its more militant phase, Rustin’s coziness with the Democratic Party power structure angered proponents of Black power. He also alienated antiwar activists when he failed to call for the immediate withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, and cautioned Dr. King against speaking out in his famous speech attacking the war delivered at Harlem’s Riverside Church. Increasingly, it seemed, Rustin took positions that put him at odds with a movement he had once so fundamentally helped to shape.

Rustin was attacked as a “pervert” or “immoral influence” by political opponents, from segregationists to Black power militants. In addition, his pre-1941 Communist Party affiliation was controversial. To avoid such attacks, Bayard Rustin served only rarely as a public spokesperson. He usually acted as an influential adviser to civil rights leaders. In the 1970s, Rustin became a public advocate on behalf of gay and lesbian causes.

In his final years, Rustin was active in the protests against the Vietnam War, and in support of the gay rights movement. He claimed in 1986, “The barometer of where one is on human rights questions is no longer the Black community, it’s the gay community. Because it is the community which is most easily mistreated.”

Bayard Rustin died in New York of a perforated appendix on August 24, 1987. He was survived by Walter Naegle, his partner of ten years. Despite the fact that he played such an important role in the civil rights movement, Rustin never fully got his due while alive, in large part because of public discomfort with his sexual orientation. However, the 2003 documentary film by Sam Pollard, “Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin,” a Sundance Festival Grand Jury Prize nominee, helped to raise awareness of his remarkable life, and his crucial contributions to the American Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

On November 20, 2013, Bayard Rustin was posthumously awarded the prestigious Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. The award was accepted by his partner, Walter Naegle. This coveted award coupled with the attention he’s received in media coverage of the anniversary of the historic March On Washington, means Rustin is finally emerging from the shadows of history, to take his rightful place as a visionary strategist, and a pioneering civil rights activist.

We remember Bayard Rustin, and celebrate him for his lifelong commitment to pacifism, social justice and civil rights, for his resilience in the face of extreme racism and homophobia, and in deep appreciation for his many contributions to our community.