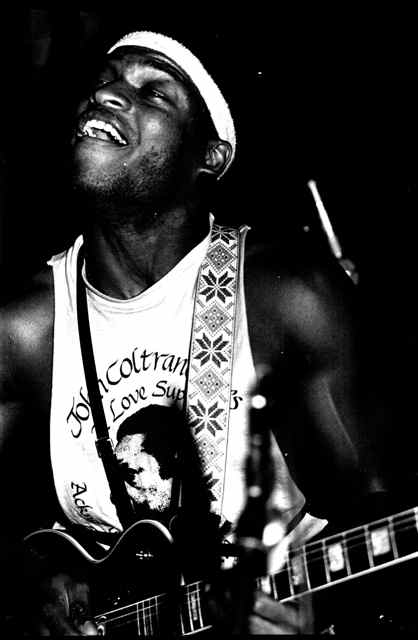

Arthur Rhames

Photo: Shigeki Masumoto

Arthur Rhames was born on October 25, 1957 (to December 27, 1989). He was an extraordinary guitarist, tenor saxophonist, pianist, melodica stylist, Krishna devotee, and a legend of New York City’s avant-garde jazz scene.

Arthur Rhames was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn to Arthur Rhames, Sr. and Laverne Ashley. He was raised in East Flatbush, along with two younger brothers, William and Clarence, and his beloved grandmother, Margaret Ashley. At age nine, Rhames took up piano and listening to classical music. During his teens, he played guitar, acoustic bass, flute, clarinet, cello, and alto saxophone. Rhames attended public schools, including Junior High School 271 in Brooklyn, and Harlem’s Music and Art High School. At one point, he studied under the tutelage of John Coltrane’s bassist Reggie Workman, who had a music school in Brooklyn in the 70s called The Muse. Arthur was its star student, and was mentored there by saxophonist Bill Barron.

Arthur Rhames was a musical prodigy who mastered the guitar, tenor saxophone, piano, and melodica (a unique wind instrument that contains a keyboard). His quest to produce the best music imaginable possessed him. According to legend, he practiced at least eight hours a day, and sometimes as many as eighteen hours each day on his various instruments. Friends recall him as being brilliant, immensely gifted, and having a photographic memory. He also became an avid bodybuilder, and approached developing his physique with the same determination and passion as he approached development of his music.

To merely say that he was the best at what he did, wouldn’t do his skills justice. Just when you thought his guitar ability was so far beyond what anybody else was capable of producing, he would pick up his tenor sax (he was often called “the reincarnation of John Coltrane”) and make grown men cry with his intense riffs and angelic performances. He was equally skilled as a pianist, and without trying, made most celebrated performers sound quaint. Rhames’ music was powerful and magical, very technically demanding, and at times it could be emotional and purposefully spiritual. It sometimes required stamina on the part of audience members, as they became mesmerized in the joyfulness of his technical wizardry, and moved to respond to its rapturous beauty.

Rhames was the consummate musician, but also largely unknown. He began his career on the electric guitar in funk and R&B acts in the early seventies. In 1972, Rhames joined a group formed by bassist Cleve Alleyne, with drummer Adrian Grannum and guitarist Clifford Pusey. Eventually, Grannum was forbidden to play by his dad because of his grades, so Alleyne and Rhames moved on, replacing Grannum with drummer Collin Young. The group became known as Eternity, and Rhames played numerous gigs in the New York City area as its guitarist, including annual shows on the Prospect Park Soundstage, and at several local colleges. Inspired by the sounds of Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report, and John Coltrane, the trio remained unsigned, despite ample word-of-mouth buzz.

They would eventually secure a series of dates opening for Larry Coryell’s fusion ensemble, Eleventh House. Although these performances won Rhames a great deal of audience acclaim, and even his own “Guitar World” profile, backstage tensions between Rhames and Coryell emerged. Coryell refused to acknowledge him as a guitarist, referring to Rhames only as “the piano player.” After five or six shows, Rhames left the tour. Nevertheless, he made a cameo appearance as a session player on Coryell’s 1978 solo album, ironically titled “Difference.”

After Eternity dissolved around 1980, Rhames and various friends could be found busking as street musicians in and around Manhattan (he frequently performed at 72nd and Columbus Avenue) with Rhames on sax and Charles Telerant on the keyboards and drums. He collaborated as a saxophonist with John Coltrane’s drummer Rashied Ali, eventually incorporating as The Dynamic Duo. They appeared at the 1981 Willisau Jazz Festival in Switzerland, and followed that with gigs in Canada and in Hagi, Japan later that year.

In October of 1981, recordings of Rhames’ former trio, including pianist John Esposito and drummer Jeff Siegel, were made at a New York club session, featuring impressive interpretations of the Coltrane classics “Giant Steps,” “Moment’s Notice,” and “Bessie’s Blues,” as well as a cover of Albert Ayler’s “I Want Jesus to Talk to Me.” They later released “Live from Soundscape” on the Japanese DIW label. Rhames was only 24 years old at that time. In 1988, he re-joined Rashied Ali in a quartet at New York’s Knitting Factory, and joined The Society for the Preservation of Intense Music for a series of concerts.

Those who knew Rhames say he was infamous for his tardiness, in addition to his tendency to respond “I’m Arthur Rhames!” whenever directly challenged about anything. Regardless of the opinions held by some who found him difficult and sometimes arrogant, he exhibited a spiritual side as well. In his Eternity period, or slightly before, he became aware of Swami Prabhupada’s expositions of Vaishnava philosophy, and his studies of the “Bhagavad Gita” strongly influenced his worldview. He worshiped at the Hare Krishna temple on Henry Street in Brooklyn (and at one point lived at a Hare Krishna temple in Manhattan), sometimes with his entire band, and wrote songs (with his bandmates) which reflected Eastern sensibilities in their titles and content, such as “Anu Dance.”

Known as “Butch” to many of his friends a colleagues, Rhames may be one of the greatest multi-instrumentalists of the last fifty years. Despite his prowess as a guitarist, alto saxophonist, and pianist, only a few recording sessions of his made it to vinyl or CD during his lifetime. He was also briefly a member of Steve Arrington’s Hall of Fame. John Esposito, who was the pianist in the Arthur Rhames Trio, says in the liner notes to “Live from Soundscape” that he performed with Rhames in at least four studio sessions between 1980 and 1987, but none of them have yet seen the light of day (although three live performances have made it to official digital release). Rhames was, according to Esposito, well-respected by, and sometime played with Pharoah Sanders, Elvin Jones, Reggie Workman, Richard Davis, and Rashied Ali, with whom he appears on “Remember Trane and Bird.”

Rhames’ lack of a recording contract with a major label made no sense to his fans. At one point, Rhames secured an appointment with an influential recording executive, someone with the power to give him the record contract he so richly deserved. He worked tirelessly to tape a performance that showcased his skills and marketability. When it was perfect, Rhames played the cassette for Charles Telerant, and they both agreed that this recording would make the difference for him. When they arrived at the appointment, they popped the tape into the player, and out came a Stevie Wonder dub that Rhames’ roommate had recorded from the radio, erasing his “perfect sample.” Thoroughly embarrassed and dejected, Rhames never rescheduled the appointment.

Rhames sometimes worked as a security guard in complete obscurity. But he played at every opportunity late in his life, and briefly toured in support of P-Funk’s George Clinton as a guitarist, after having shown up to audition in his security uniform.

Some musicians who worked with Rhames knew that he was gay, and it seemed to matter to none of them. He also appears throughout most of his life to have been deeply closeted, and at least one source claimed that he was fearful of losing his fans if they knew about his same-gender attractions. Rhames had relationships with a few boyfriends, but he was actually rather shy, and often a loner who transformed himself when he was performing before an audience.

Toward the end of his life, Rhames was very ill and frequently hospitalized with different medical conditions caused by AIDS. Arthur Rhames was only 32 years old when he died of AIDS-related complications in a Newark, New Jersey hospital just after Christmas in 1989. He was interred at the Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey.

Rhames was one of the most skillful musicians to emerge in the latter half of the twentieth century. Except for his acclaim from colleagues in the music world, he died in relative obscurity, and without ever securing a major recording contract. His friend and frequent musical collaborator, Charles Telerant, related shortly after Rhames’ passing that once he was sitting in the office of Brian Bachhus, the vice president of A&R at Verve Records at the time. When asked by Bachhus who he had played with, Telerant responded, “A guy from Brooklyn named Arthur Rhames.” Bachhus practically screamed, “Arthur Rhames? You played with Arthur Rhames? Where can I find him? I’ll sign him right now!” Telerant replied, “You can’t, Brian. Arthur died three weeks ago.”

Arthur Rhames is becoming much better known today through praise from musicians with whom he worked, and newfound fame through YouTube and other websites. A good resource is a site dedicated to his memory, lovingly maintained by his dear friend Cleve Alleyne.

We remember Arthur Rhames for his brilliant creativity, his commitment to preserving and promoting jazz, and his many contributions to our community.