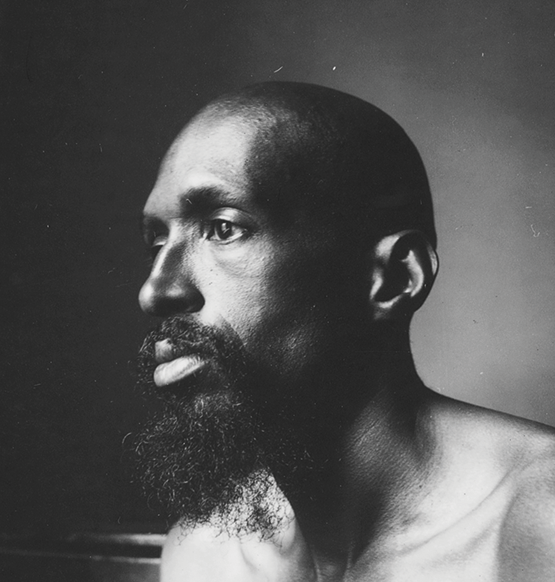

Julius Eastman

[The references to “I” in this biography are Stephen Maglott, the original author]

Julius Eastman was born on October 27, 1940 (to May 28, 1990). He was an accomplished composer, pianist, vocalist, and dancer of minimalist tendencies.

Julius Eastman grew up in Ithaca, New York, where he worked in his teen years as a paid chorister. He gained plenty of regional attention with his wonderful voice, and began his piano studies at age 14. After only six months of practice, he was playing Beethoven and other challenging classical composers. Eastman attended Ithaca College and transferred to the Curtis Institute of Music, where he studied piano with Mieczyslaw Horszowski and composition with Constant Vauclain. After a few months, Eastman switched his major from piano to composition.

Eastman made his debut as a pianist in 1966 at Town Hall in New York City. He possessed a rich baritone voice that caught the attention of the symphonic world when he recorded the 1973 Grammy-nominated Nonesuch recording of British composer Peter Maxwell Davies’ “Eight Songs for a Mad King.” Eastman’s talents as a composer impressed the celebrated composer and conductor, Lukas Foss.

In 1970, Eastman joined the Center for the Creative and Performing Arts at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he met the Czech-born composer, conductor, and flutist Petr Kotik. Eastman and Kotik performed together extensively in the early to mid-1970s, and he became a founding member of the S.E.M. Ensemble, with whom he performed, toured, and composed numerous works. Many of the earliest performances of Eastman’s works were given by the Creative Associates Ensemble of University at Buffalo, of which he was also a member beginning in 1968. He taught theory while at the University at Buffalo, but left over what he described as “creative differences.” Eastman had hoped to transition to a similar position at Cornell University, in his hometown of Ithaca, but they quickly backed away, and it failed to materialize.

Eastman eventually moved to New York City, where he was associated with the Brooklyn Philharmonic, then led by his friend Lukas Foss. Eastman became a pioneering figure in minimalism, and an influential member of the 1980s Downtown New York scene. He performed in jazz groups with his brother, Gerry Eastman, a guitarist and bass player in many jazz ensembles, including the Count Basie Orchestra. Ironically, the only work by Julius Eastman registered with the U.S. Copyright Office is as a lyricist, with his brother Gerry listed as the composer.

Julius Eastman was a composer of works that were minimal in form but maximal in effect. His compositions were often written according to what he considered an “organic” principle, by which each new section of a work contained all the information from previous sections, though sometimes “the information is taken out at a gradual and logical rate.” The principle is most evident in his three works for four pianos, “Evil Nigger,” “Crazy Nigger,” and “Gay Guerrilla,” all from around 1979.

The last of these, an expansive and emotional work, appropriates Martin Luther’s hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” as a gay manifesto. Eastman’s “Stay On It” from 1973 was an influential post-minimalist piece that incorporated pop music influences. He frequently performed with the Experimental Intermedia Foundation, and participated in music symposia with Morton Feldman and John Cage.

A 1980 selection for Eastman’s voice and cello ensemble, “The Holy Presence of Jeanne d’Arc,” was performed at The Kitchen in New York City, and he lent his vocal strength to Meredith Monk’s ensemble for her influential album, “Dolmen Music,” in 1981. In 1986, choreographer Molissa Fenley used his work “Thruway” for a dance called “Geologic Moments” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Julius Eastman was a man seemingly balanced between irreconcilable extremes. He was brilliant, but suffered from extreme bouts of schizophrenia; he was celebrated as a star in the avant-garde world of classical music, but was occasionally homeless and sleeping in Manhattan’s Tompkins Square Park. But perhaps the greatest difference was addressed by one of Eastman’s colleagues who stated simply, he was “a Black, gay man rattling around loudly in the white, constrained world of classical music. Eastman was a living testament to unbounded American opportunity and woeful American inequality.”

Eastman’s mercurial artistry often reflected those conflicting paradigms in his world. His compositions exposed a confrontation that he saw between Western and African music, and conflicting notions of beauty. Eastman’s music could comfort one moment and agitate the next. But in the end, he may have been a man who despite his immense intellect and talent, thrashed himself apart trying to live too many contradictions.

Eastman also battled alcoholism and drug addiction. He could be immensely charming, but also an acrid, seething, and occasionally impossible man. Sometimes when he spoke, it was difficult to detect if he was being hurtful or humorous. His temperament can even be detected in the titles he assigned his compositions: “If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich,” “Evil Nigger,” and “Gay Guerrilla.” The language was so acidic, it ate away at the concert hall universe, and was perhaps a fitting gesture for someone who saw as much rank hypocrisy as opportunity within its walls.

Despondent about what he saw as a dearth of professional possibilities worthy of him, Eastman grew increasingly dependent on alcohol and other drugs after 1983, and his life began to fall apart. At one point, he was evicted from his apartment, his belongings (including most of his music scores) abandoned curbside. Despite an unsuccessful attempt at a comeback, he shuffled between friends’ homes in New York City and Buffalo, and slipped into obscurity.

Julius Eastman and I had a mutual friend, upon whose doorstep Eastman would occasionally appear. He would stay for a while, and then vanish under the premise of a new musical collaboration or project that required his presence. His friend, John Crawford, had a spacious apartment in a very elegant rowhouse in downtown Buffalo. He also had a stunning, burled rosewood Steinway Grand in his parlor, that Eastman reportedly never touched. It appears his disconnection from his musical past was becoming complete.

At his final visit to Buffalo, Julius Eastman was very, very ill. I spoke to him briefly, but was disturbed to see him in such deep crisis. He suffered from insomnia, was emotionally distressed, and, as I recall, very paranoid—certain that the music world was out to destroy him. But the more pressing issue was his rapidly failing health from the effects of AIDS. Within days, Eastman would be rushed to Buffalo’s Millard Fillmore Hospital, where he died three days later, on May 28, 1990, from AIDS-related, cardiac arrest. Julius Eastman had descended so far from the public eye that no notice was given to his death until an obituary by Kyle Gann appeared in the “Village Voice” on January 22, 1991, eight months after he died.

Eastman’s notational methods were loose and open to interpretation, and consequently, any revival of his music has been a difficult task, dependent on the generous efforts of people who worked with him. Many of his compositions and recordings were discarded when he was evicted. But there are some amazing musicians, who are working tirelessly to collect, preserve, and perform his compositions, and keep his unique musical presence available for generations to come.

Eastman’s music continues to be heard around the world. In December of 2016, the world’s first Eastman retrospective took place at the London Contemporary Music Festival, and included a presentation of seven Eastman works and an exhibition, spread over three nights. The following May, “That Which Is Fundamental,” a four-concert retrospective and month-long exhibition of Eastman’s work was hosted at Bowerbird in Philadelphia, produced in collaboration with the Eastman Estate.

We remember Julius Eastman, and thank him for his unique artistry, and his contributions to our cultural landscape and community.