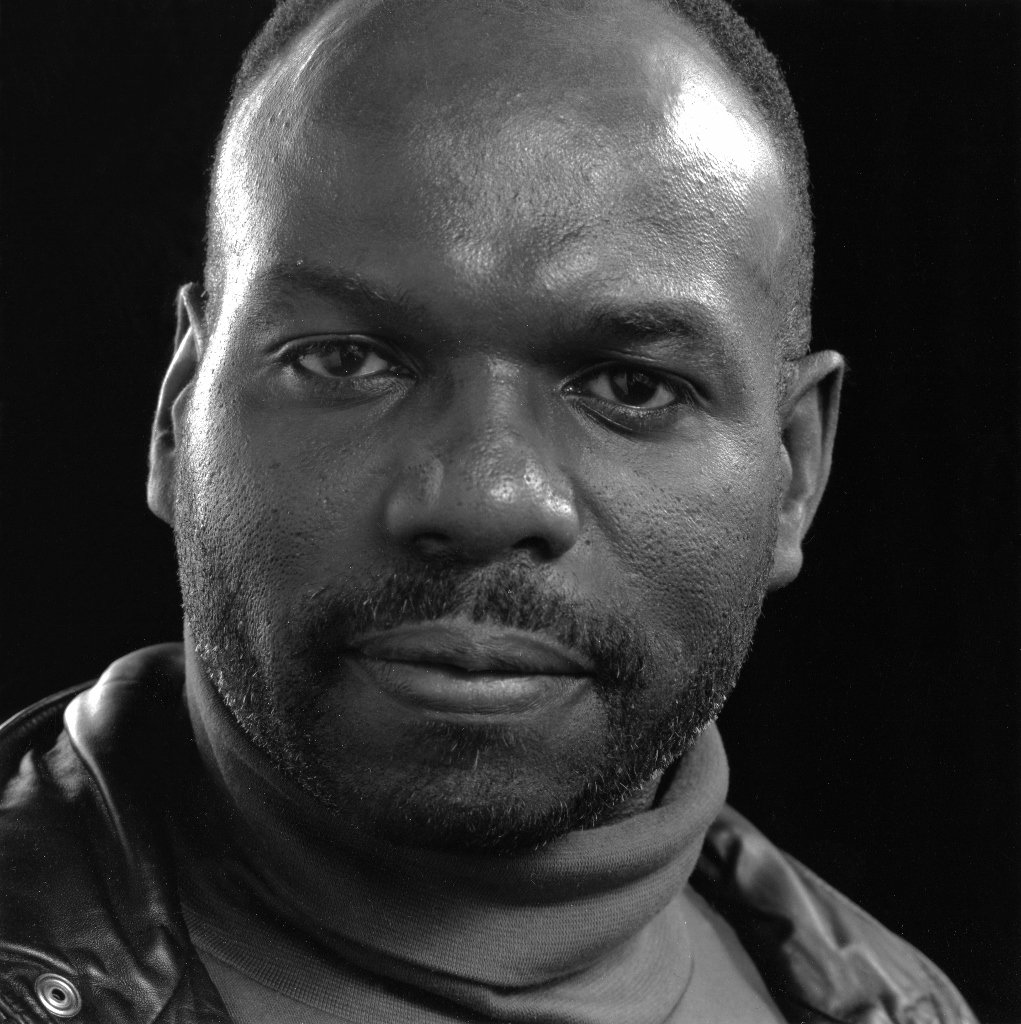

Marlon Riggs

Marlon T. Riggs was born on February 3, 1957 (to April 5, 1994). He was a groundbreaking filmmaker, educator, poet, and gay rights activist, best known as the producer, writer, and director of several television documentaries, including “Ethnic Notions,” “Tongues Untied,” “Color Adjustment,” and “Black Is…Black Ain’t.”

Marlon Troy Riggs was born in Fort Worth, Texas, to Jean and Alvin Riggs, who were civilian employees of the military. He spent much of his childhood traveling, and lived in Texas and Georgia before moving to West Germany with his family at age 11. Riggs would recall that Black and white students alike called him “punk,” “faggot,” and “Uncle Tom” when he was a student at Hephzibah Junior High School in Hephzibah, Georgia. He explained his feelings of isolation from everyone while at the school: “I was caught between these two worlds where the whites hated me and the blacks disparaged me. It was so painful.”

From 1973 to 1974, Marlon Riggs attended Ansbach American High School in Katterbach, Germany, where he was elected student body president at the military dependents school. In 1974, he returned to the United States to study history at Harvard University on a full scholarship, and graduated magna cum laude in 1978. As Riggs began studying the history of American racism and homophobia, he became interested in communicating his ideas about these subjects through film.

After working for a local television station in Texas for about a year, Riggs moved to Oakland, California, where he entered graduate school. He received his master’s degree in journalism with a specialization in historical documentary filmmaking in 1981 from the University of California at Berkeley, having co-produced and co-directed with Peter Webster a master’s thesis titled “Long Train Running: The Story of the Oakland Blues.”

After finishing graduate school, Riggs began working in public television. His first projects included short documentaries on the American arms race, Nicaragua, Central America, sexism, and disability rights. In 1987, Riggs was hired as a part-time faculty member at the Graduate School of Journalism at Berkeley to teach documentary filmmaking. He became a tenured professor at Berkeley shortly thereafter.

That same year, Riggs completed his first professional feature documentary, “Ethnic Notions.” The film was produced in association with public television station KQED in San Francisco, and aired on public television stations throughout the United States. In “Ethnic Notions,” he sought to explore widespread and persistent stereotypes of black people—images of ugly, savage brutes and happy servants—in American popular culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Riggs’ use of knowledgeable narration and expert testimony gave the film an academic rather than a personal perspective.

While he continued working as an educator at Berkeley, Riggs kept making his own films. The 1989 film “Tongues Untied,” a highly personalized and moving documentary about the life experiences of gay African American men, was aired as part of the PBS television series “Point Of View” (P.O.V.). The film employs autobiographical footage as well as performance, including monologues, songs, poems, and nonverbal gestures to convey an authentic and positive Black gay identity. It was the first frank discussion of the Black, gay experience on television.

In 1988, while working on “Tongues Untied,” Riggs was diagnosed with HIV after undergoing treatment for an unrelated kidney ailment at a hospital in Germany. The film shows the pain as well as the mentally and physically agonizing therapy that Riggs had to endure in order to deal with his terminal illness. But despite his deteriorating health, Riggs decided to continue to teach at Berkeley and make documentaries. He was quoted as saying, “I began to see the consequences of silence.” “Tongues Untied” would break that silence—and then some—from and around Black gay men by demanding they be seen, acknowledged, and no longer marginalized by their own communities for being who they are.

Though acclaimed by critics and awarded Best Documentary at the Berlin and other film festivals, the broadcast of “Tongues Untied” was immediately pounced upon by the religious right as a symbol of everything wrong with public funding for art and culture, particularly culture outside the mainstream. Riggs had received $5,000 from a National Endowment for the Arts regional re-granting program, and “P.O.V.” had received both NEA and Corporation for Public Broadcasting funding.

The Christian Coalition edited a highly sensationalized seven-minute clip from the film which they sent to every member of Congress. Homophobe and avowed segregationist Senator Jesse Helms became the point man for the chorus of denunciation. In a telling Freudian slip, he invariably referred to the film as “Tongues United,” Then, Christian extremist Patrick Buchanan re-edited a 20-second clip from the film for a sensationalized TV ad hit piece blasting the NEA during the 1992 presidential primary. Riggs responded with an op-ed in “The New York Times.” “The insult,” Riggs wrote, “extends not just to blacks and gays, the majority of whom are taxpayers and would therefore seem entitled to some means of representation in publicly financed art. The insult confronts all of us who witness and are outraged by the quality of political debate.”

The three principle voices of “Tongues Untied” are those of Riggs as well as HIV positive gay rights activists Essex Hemphill and Joseph Beam. Riggs characterized the film as his legacy, his “last gift to the community” that displays him as both a filmmaker and a gay rights activist. He described the production as his own personal “coming out” film celebrating Black gay life experiences, and that he ultimately became “the person, the vehicle, and the vessel” for these experiences. The end of “Tongues Untied” included a memorable triumph: Riggs in close-up proclaiming, “Whatever awaits me, this much I know: I was blind to my brother’s beauty, and now I see my own,” followed by the onscreen text “Black men loving Black men is THE revolutionary act.”

Cornelius Moore, the co-director of California Newsreel, the distributor of Marlon T. Riggs’ films, knew Riggs as a professional colleague, and as a dear friend, and he served as the executor of his estate. He had this to say when asked about the impact of Marlon Riggs’ work; “I remember how excited and dedicated Marlon was to the idea of doing something about Black gay life in a way that was non-conventional. His initial plan was to make a short experimental piece for Black gay audiences to be shown in clubs and community centers. However, it became a longer film that had an impact beyond that, including a theatrical release and a national broadcast on PBS. And he incorporated the works of a community of artists—most notably Essex Hemphill, presenting both pain and joy at a time when the AIDS epidemic was ravaging the community.”

In the short 1990 piece “Affirmations,” Riggs further developed his critique of homophobia that he originally expressed in “Tongues Untied.” In 1991, he directed and produced “Anthem,” a short documentary about African American male sexuality. The film includes a collage of erotic images of Black men, hip-hop music, and a call to celebrate difference in sexuality. The 1991 documentary “Color Adjustment” was his second film to air on the PBS television series “P.O.V.,” and served as a follow-up to “Ethnic Notions,” focusing on images of Black people in American television from the mid-1940s through the 1980s. “Color Adjustment” presents a cultural criticism of these images through an African American perspective on race. The film is narrated by African American actress Ruby Dee. Using contemporary interviews of television actors, directors, producers, and cultural commentators, the documentary conveys personal reflections and academic analyses of such television programs as “Good Times” and “The Cosby Show.”

In 1992, Riggs directed the film “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regret),” a short independent documentary about dealing with AIDS personally, and the impact it has on the gay Black male community. Using poetry, music, and candid interviews, the film tells the stories of several Black gay men who have been diagnosed with the disease. In 1993, Riggs received an Honorary Doctorate degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts. That same year, his documentary “Anthem” was featured in a collection of short films entitled “Boys’ Shorts: The New Queer Cinema.”

In addition to his landmark documentaries and teaching at Berkeley, Riggs wrote both poetry and essays, many of which were published during the late 1980s and early 1990s in various art and literary journals such as “Black American Literature Forum,” “Art Journal,” and “High Performance,” as well as anthologies such as “Brother to Brother: Collected Writings by Black Gay Men.” The themes of his writings include filmmaking, free speech and censorship, and criticism of racism and homophobia.

Riggs began work on his final film “Black Is…Black Ain’t” in 1994. However, several months into developing the film, Riggs became critically ill, and was immediately hospitalized in order to boost his autoimmune system as part of his AIDS treatment. Much of the final text of “Black Is…Black Ain’t” was developed by Riggs one night in his hospital room. The documentary takes on the topic of African American identity, including considerations of skin color, religion, politics, class stratification, sexuality, and gender difference that revolve around it.

Marlon T. Riggs succumbed to AIDS on April 5, 1994. He left behind a remarkable legacy of critical thought and advocacy on film that has influenced and impacted the lives of so many around the world. He is survived by his partner of fifteen years, Jack Vincent, and his parents Jean and Alvin Riggs, and his beloved sister, Sascha.

“Marlon’s life was unfortunately short,” added Cornelius Moore, “but he produced an extraordinary and lasting body of work in the time he was here. He highlighted diversity within African American communities in his award-winning final film, ‘Black Is…Black Ain’t,’ and examined historical representation of Black people in ‘Ethnic Notions’ and ‘Color Adjustment.’ His groundbreaking personal and experimental documentary ‘Tongues Untied’ was very important for giving voice and imagery to the experiences of gay men in Black America.”

Riggs received a National Emmy Award in 1987. In addition to the award that “Tongues Untied” received for Best Documentary at the Berlin Film Festival, it received recognition from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, the New York Documentary Film Festival, the American Film and Video Festival, and the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. In 1992, Riggs was awarded the Maya Daren Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute. Additionally, “Color Adjustment” won the prestigious George Foster Peabody Award, the Erik Barnouw Award from the Organization of American Historians, the International Documentary Association Outstanding Achievement Award, and a premier screening at the Sundance Film Festival.

Riggs also received the Frameline Award from the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival for his film “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regret).” Moreover, “Black Is…Black Ain’t” won the Golden Gate Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival, and the Filmmaker’s Trophy at the Sundance Film Festival. In 2003, the San Francisco Film Critics Circle created the Marlon Riggs Award for courage and vision in the Bay Area film community. The award is intended for Bay Area artists or exhibitors who have made considerable contributions to the art of film. Riggs was inducted into the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association Hall of Fame in 2006.

We remember Marlon T. Riggs, and thank him for the impact of his skillful artistry, for his groundbreaking activism, and for his many contributions to our community.