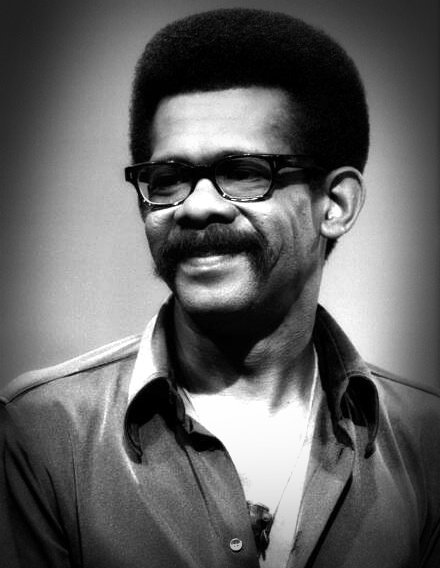

Ellis Haizlip

Ellis Haizlip was born on September 17, 1929 (to January 25, 1991). He was a pioneering broadcaster, television host, theater and television producer, and cultural activist.

Ellis Haizlip was born in Washington, DC. Details of his early life are elusive, but rumors have persisted that his father was a diplomat who once served as the ambassador to the Court of St. James from Antigua (other accounts claimed Trinidad) and he may have spent many of his formative years in London. He told friends that he grew up in segregated Washington DC, and had had witnessed contralto Marian Anderson’s legendary 1939 concert on the steps on the Lincoln Memorial. We do know that he attended Howard University and graduated from there in 1954.

While at Howard, Hazlip served as a producer for the Howard Players, the acclaimed performance art troupe of Howard University’s Department of Theatre Arts, during their summer season. After graduating, he left for New York City, where he began producing plays with Vinnette Carroll at the Harlem YMCA. One of their productions was “Dark of the Moon,” with Cicely Tyson, Clarence Williams III, Isabel Sanford, Calvin Lockhart, James Earl Jones, and the Alvin Ailey Dancers.

Through the 1950ss, Ellis Hazlip produced concerts and performances in Europe and the Middle East. These included “Black New World” by dancer Donald McKayle; “The Amen Corner” by his friend James Baldwin; and “Black Nativity” by Langston Hughes. He also produced a concert tour by Marlene Dietrich.

In 1972 and 1973, Haizlip and Lincoln Center produced “Soul at the Center,” an acclaimed 12-day festival of Black expression through the performing arts. Other groundbreaking Haizlip productions were the first Congressional Black Caucus Dinner in 1970, “Welcome to the World Saxophone” in 1980, and “Watch Your Mouth!” in 1978 for WNET Channel 13, New York’s flagship Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) station, where he served from 1967 to 1981.

Ellis Hazlip was encyclopedic in his knowledge of the world of African-American arts and letters, and he knew hundreds of key players. He used his wealth of knowledge as the coordinator of cultural activities for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Hazlip is best known as the host and producer of a unique and radically Afrocentric program for PBS simply called “Soul!” which ran from 1967 through 1973. As executive producer, Hazlip is credited with helping to advance the careers of singers Nicholas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, and Roberta Flack and Novella Nelson.

“Soul!” was the brainchild of Haizlip, the first Black producer at WNET (then WNDT), who joined the station in the mid-1960s. He was approached by the station’s white director of cultural programming with the idea of launching an arts program for Black audiences. Haizlip’s vision was for a program that would use the variety show format to display the breadth and variety of Black culture. The mission of “Soul!” mission would be not merely to entertain African American viewers, but to challenge them to ponder the possible meanings of Black culture and Black community at a time when African Americans were driving America’s social transformation.

Initial funding for “Soul!” came from a combination of public and private sources, including a startup grant from the Ford Foundation. With money in place, Ellis Haizlip pulled together a creative team of camera operators, set designers, and producers, the majority of whom were African Americans. Alice Hille, the first associate producer of “Soul,” and one of the first Black women to hold such a position, became Haizlip’s close collaborator and, through her connections to Harlem’s Apollo Theater, his link to the rhythm and blues world. For Haizlip, opera singers, funk musicians, lyrical poets, and political revolutionaries were equal participants in the Black cultural project. Haizlip’s philosophy was “it’s all our culture,” recalls Anna Maria Horsford, who worked as an associate producer at “Soul!” “It was a celebration. Look what we’ve produced in spite of.”

Perhaps more than any other television show before—or since, “Soul!” insisted on representing the heterogeneity of Black culture. It embraced cultural nationalists, Muslims, and feminists—occasionally on the same show. It flouted the conventional wisdom that ballet dancers and blues singers could not share a stage, let alone an audience. In addition to championing emerging acts, such as Ashford and Simpson, who appeared on the show before they issued their first album, “Soul!” embraced radical and challenging improvisatory music from multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk, jazz drummer Max Roach, and the genre-defying Last Poets.

“Soul!” also gave artists a chance to go beyond their usual roles, and relished the unexpected juxtaposition. Among the most intriguing “Soul!” pairings: Bill Withers, the hit-making singer-songwriter, with poet Mae Jackson; Reverend Jesse Jackson (then best known for his work with PUSH) with former Raelette (Ray Charles’ backup singers) Merry Clayton; award-winning author Toni Morrison with Junior Walker and His All-Stars; Louis Farrakhan with musicians Mongo Santamaria and the Delfonics; singer Jerry Butler with boxing champ Muhammad Ali; and Sidney Poitier with Stevie Wonder and poet Nikki Giovanni. Most importantly, “Soul!” was unapologetic about aiming its diverse and self-critical weekly affirmation of Black culture and politics to African American viewers, a group that had previously not had the pleasure of seeing itself widely, or truthfully, represented on television.

“Soul!” was “taped as live,” which allowed its camera operators to capture reactions of a modest studio audience made up of local New Yorkers. Indeed, in making the audience part of the spectacle, Haizlip brought to television the aesthetic principles he had imbibed in the churches of his youth, and he was able to represent Black music as a conversation, an exchange, between the musicians and show’s audience.

In an era when “being out” had yet to catch on, and previous to the Stonewall riots which would catalyze the gay and lesbian liberation movement, Ellis Haizlip was a Black gay man and an important public figure in America’s Black cultural landscape. He was not “out” as we understand the concept today, and his presence was said to be “tolerated” by executives at Channel 13 who were uneasy with Haizlip’s presence, and worried that a gay man wasn’t an appropriate or fitting on-camera embodiment of Black masculinity. While not out to the general public, neither did he shy away from gay community issues. When Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan appeared on “Soul!,” Haizlip boldly asked him whether the Nation of Islam welcomed Black gays and lesbians, and reminded Farrakhan that many Black people had experienced conversion to the Nation while in prison.

As the 1960s gave way to the ’70s, Ellis Haizlip and others at “Soul!” came under increasing pressure to tamp down the show’s message of Black pride. From the beginning, “Soul!” had to fight for its survival. In 1970, with viewers pleading for the show to stay on the air, a three-year, $3.5 million grant from the Ford Foundation saved the program. But the January 1969 transfer of presidential power from Lyndon Johnson—whose administration had created PBS—to Richard Nixon, meant a new set of priorities for public broadcasting. By the end of 1972, Corporation for Public Broadcasting officials had deemed Black shows such as “Soul!” hindrances to racial progress. Haizlip was given a choice: integrate “Soul!” or see it cancelled. The last episode aired on March 7, 1973.

For reasons unconnected with Haizlip’s sexuality, “Soul!” ran out of funding before he could be replaced, despite its popularity among audiences. From the beginning, critical reviews of the show had been strong, and “Soul!” had been quick to develop a following, first locally in New York, then nationally when the Corporation for Public Broadcasting picked the show up for syndication. Even though it only aired for five seasons, “Soul!” never lacked popular support. Ironically, perhaps, the defunding of “Soul!” made room for the commercial Black television shows of the 1970s. The existence of those shows and of more Black television characters would generate new questions regarding the relationship between visibility and Black “progress.”

In the 1980s, Ellis Hazlip was diagnosed with lung cancer, and then a brain tumor; his friends, guests and colleagues were devastated. A year before his death, there was a benefit to help pay his medical expenses, attended by Ashford and Simpson, Betty Shabazz and Roberta Flack, and dozens of other notables and close friends. He lost his battle against cancer at the age of 61, on January 25, 1991. His memorial service was held at Harlem’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where he was eulogized by his friend, Amiri Baraka, and New York City Mayor David A. Dinkins, with a special performance by Alvin Ailey’s dancers.

Ellis Haizlip and his groundbreaking program “Soul!” were honored with a documentary celebrating the contributions of this pioneering PBS program. “Mr. Soul! The Movie” was directed by Samuel D. Pollard and Melissa Haizlip. A special thanks to Melissa Haizlip for her input in correcting errors in a previous edition of this biography.

You can read more about Ellis Haizlip here (which contains material written by Gayle Wald that was used for this biography. Wald’s book, “It’s Been Beautiful: Soul and Black Power Television” was published by Duke University Press in 2015).

We remember Ellis Haizlip in appreciation of his promotion of Black culture and the arts, his uncompromising advocacy for America’s Black history, and for his many contributions to our community.